|

14/1/2019 1 Comment "who do you say I am?"Jacob Wrestling the Angel by Roy de Maistre (1894-1968). Courtesy of Charles Nodrum Gallery, Richmond, Australia. “But you, who do you say I am?” Jesus asks his disciples in Matthew 16:15. This question,” Who do you say I am?” is asked of us by God’s eternal Word which speaks unceasingly in our souls. Our entire faith can be condensed into this single question and our response to it.

Every situation that we encounter, every anxiety we confront, every decision we face, every relationship we enter, will be shaped by our response to that eternal question. In joy, in grief, in fear, in anger, in doubt, we need to turn inward and listen to that question being asked. Our response will guide us more surely and truly than we can possibly imagine. The journey I have been making over the past many years is as unique to me as your personal journeys are to you. Many of the parts which go to make up my journey will be very familiar to others: it is the sum of those parts which will be unique in each case. Last November, this blog described the spiritual desolation my mother endured in her final illness. Through those pitiless days I watched her go, as it seemed, into unrelieved darkness. However, in her final hours, I found myself identifying across two millennia with another person bent under a cross not his own. Simon of Cyrene made a crooked way straight for me and helped me see the Easter Sunday that lies beyond every Good Friday. This was the first in a series of Biblical encounters which were to mark my very contemporary life profoundly. In today’s western world technology gives a false sense of connectedness – we can travel anywhere and we are never out of touch. The reality is that we are probably more alone now than at any stage in our history. However much and easily we move across the surface of the world, we no longer seem to put down roots. We are no longer connected with a place and a community in the way our ancestors were. The notion of drawing from a shared past has become alien to us; but we can become so easily enslaved by our own past, our past failures especially, which can drain us of confidence in our ability to move forward. The journey we make from birth to death and rebirth has been made over and over again for 50,000 years. Nobody can make it for us, even though countless people have made it before us.While only I can walk my own journey, I do not need to walk alone. In any journey, it helps to have a guide – someone who has gone that way before. If you have been following this blog, you will know that I often retrace different stages of my own life’s journey in varied and illuminating company. With Simon of Cyrene, I found myself part of an ancient community of memory. The Bible, bought by many but read by few, provides me with many other travelling companions in times of confidence and terror, exhilaration and discouragement, self-love and self-loathing, clarity and confusion. For, while each of our journeys is deeply personal, elements in each are also elements of the journey of Everyman. The people I encounter in the pages of the Bible are an extraordinary collection – ranging from wholly lovable to deeply unpleasant. Their journeys incorporate elements which embrace the tragic and the uplifting, the terrible and the playful. All have this in common – the experiences these people lived, the conflicts they encountered, the routes they mapped, are as relevant today as they were when their stories were first told. “Who do you say I am?” With Eve and Mary, I replied joyfully, “you are God who is forever young and forever new. You have put flesh on my dry bones and breathed life into me. With you I participate in the ongoing act of Creation. Through you I make my soul throughout all my earthly days.” In the majestic lifelessness of the Judean wilderness, I reply with Moses, “You are the one who rains down grace and makes the wilderness bloom. You make my interior landscape holy”. With Jonah, I turned away from what I knew I should do and sought safety in numbness. I found that it is possible to come back from the land of no return and to change your judgement. I answered you, “You are the one who sometimes chooses to use me as a conduit for your transforming grace”. I stood with Lot’s wife looking down on the cataclysm that was her former life, and I felt the salt on her cheeks. Though her experience I discovered that my life is a freely flowing focus of action in which the only thing that can stop me is the belief that I am not free. In the temple at Shiloh, Hannah’s triumphant and prophetic canticle showed me how the ending of one story is always the beginning of another. In our children we must willingly become a channel for God’s transformative work. At Simon the Pharisee’s table, I took courage from the nameless woman who washed the feet of Jesus and discovered that in order to love others one must first forgive oneself. I watched David dancing with all his might before you, and I heard you speak to Job. My heart was lifted within me and I found I could exclaim with Peter, “Lord, it is wonderful for me to be here!” In Jacob, a man for all times and all seasons, I learned to embrace crisis in the original sense of the word as a turning point – something to be welcomed rather than feared, something that the philosopher Ivan Illich described as the "the marvellous moment when people become aware of their self-imposed cages, and of the possibility of a different life".[1] With these ancient companionss, I make the exhilarating discovery that my journey is endlessly beginning; that I have the possibility - in Teilhard de Chardin's words - of "making my own soul" every day of my life; and that birth and rebirth are an astonishing adventure in which the soul never ages. [1] Ivan Illich, The Right to Useful Unemployment, London, Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd., 1996, p. 20.

1 Comment

11/11/2018 1 Comment A Deathbed encounterSimon of Cyrene Helps Carry the Cross of Jesus. Painted by Ken Cooke. Courtesy of Church of St George the Martyr, Wash, Newbury, UK. I met Simon of Cyrene at my mother's deathbed, where I had been keeping a vigil for many long days. I remember the rain, the dark, the quiet. The open window and the rain falling like comfort. I listened to her breathing and watched her – the skeletal body with the powerful heart, the heart that would not let her die. Her hand, so beautiful still, lay on the smooth cover of the bed. My mother could no longer swallow. I had a supply of small sponges which I used to moisten her parched lips. In that sickroom, the shadow of Calvary cast such a deep shadow that the resonance of the gesture was inescapable, “they put a sponge full of vinegar on a branch of hyssop and held it to his mouth”.[1] Another, even older voice, sounded in my ears, “I am worn out calling for help; my throat is parched. My eyes fail, looking for my God.” [2] Three times before she sank into the final coma, she whispered “My God, my God, why abandonest thou me?” My mother had been a beautiful, energetic and gregarious woman, with many interests. She was a daily Mass-goer throughout her long life and really lived her faith. Her house and her heart were always open to anyone in need, and she radiated encouragement and hope. It was only in her later years that I came to know that the hope she gave to others was not often something she experienced herself. Yet there very few among her large circle of friends who suspected how much her faith was a willed thing and not a gift from God. As she approached the end of her life, she became possessed by an unrelenting terror of death which increased dramatically in her final illness. “My God, my God, why abandonest thou me?” The archaic language was that of her childhood. When she reached for a concept of God, it was the God of her far-off schooldays – an Old Testament God of judgement and retribution. Her religion, practised so faithfully over so many years, brought her no solace. No glimmer of comfort could touch her. In that small room, I watched her world contract. Terror filled her mind to the exclusion of almost any other emotion. Yet, when I would arrive in her room, she never failed to recognise me. Her eyes became a blazing glory of love. All her former strength and hope lived once more in that shining gaze. Then the darkness took hold of her again. And of me. Together, we took her cross up again. It was there, in that quiet room, that I gazed across the space of two millennia and saw him, another person bent under a cross not his own. Another person on a seemingly hopeless journey. Simon of Cyrene. Cyrene was an ancient Greek colony, beautifully set in a fertile valley beneath the wooded uplands of Jebel Akhdar in what is now north east Libya. The 7th Century BC Greeks who settled Cyrenaica, fleeing drought in their home island of Thera, were directed to this spot by Berber tribesmen who told them that there was a “hole in the heavens” here. Through this “hole” abundant and life-giving rain fell to create a lush expanse in the wastes of the Sahara. Pressed into service by the flat of a Roman spear, we can be sure that Simon of Cyrene did not welcome his arduous and humiliating task. Yet at this moment in time, all unknowing, Simon – like the founders of his native city seven centuries earlier - is standing under “a hole in the heavens”. The blood and sweat which rain down on him will transform his life. One would have expected Simon to put the memory of his horrible experience behind him as quickly as possible, but his two sons, Alexander and Rufus, will become sufficiently prominent in the young Christian church to be mentioned by Mark and Paul ((Mk 15:21; Romans 16:13). In shouldering his burden, it seems that Simon discovered that sometimes it is enough just to be in Christ’s presence, “I was found by those who did not seek me. I have shown myself to those who did not ask for me.” [3] Just at this point of Simon’s journey, however, there can be no glimpse of what is to come. The journey from Jerusalem to Calvary begins and ends in darkness. The suffering is unmitigated, the sadness unrelieved. Christ’s own words from the cross seem to be a cry of despair. “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” As I sat with my mother though those pitiless days, I longed for some hint of deliverance, some faint intimation of the Easter that lay beyond Good Friday. I longed for it for myself as well as for her. I couldn’t bear to see her go into unrelieved darkness. There was no evident light for my mother on her last journey. No light for Simon of Cyrene. No light for Christ as he struggles to his place of execution. But the hill of Calvary is also an altar. The victim is also the priest: his death is simultaneously sacrificial and redemptive. When all seems lost, Christ can still say to the crucified thief “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise”. I sat by my mother as Simon probably stood at the foot of the Cross. Simon can have no reason to believe that he is seeing things any way other than they actually are. He is looking at a crucified man, hearing his cry of despair. He watches him die, with no alleviation of his suffering. He watches the breath go out of the crucified man and probably asks himself, as I was asking myself, “what was it all for?” I kept thinking about the dim figures of Alexander and Rufus. If they had become committed Christians it must have been as a result of their father’s brief encounter with Christ on that Good Friday. And I, who had encountered Christ countless times in the Eucharist, could sit by my mother on her Good Friday and not see any Easter Sunday beyond. I listen again with Simon to that terrible cry from the Cross, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” This time I listen somewhat differently. I place Good Friday in the context of Easter Sunday and I place Christ’s words in the context in which they were written. They are the opening words of Psalm 22, and any devout Jew at the foot of the Cross would have known how the Psalm continued. It goes on to describe in graphic detail the nature of the death the Messiah will undergo, and it ends with the ringing proclamation, “Posterity shall serve him; men shall tell of the Lord to the coming generation and proclaim his deliverance to a people yet unborn.” Far from being a cry of despair, it is a shout of triumph. Like Simon, I was present under a “hole in the heavens” without knowing it. What was falling into that room wasn’t the rain which fell onto the desert in ancient Cyrenaica, nor the sweat and blood of Christ which fell upon Simon of Cyrene, but something as fruitful and redemptive as either. It was what John of the Cross described as the dark waters close to God in which the striving soul is hidden and protected, “The soul, though in darkness, travels securely because of the courage it acquires as soon as it enters the dark, painful and gloomy waters of God. Though it is dark, still it is water, and it can only refresh and strengthen the soul in all that is most necessary for it, though it does so painfully and in darkness…Thus the soul goes forth out of itself, away from all created things to the sweet and delightful union of the love of God, in darkness and in safety”.[4] In that room, over those weeks, I came to realise that what we feel is not always important. I prayed for the grace to place myself in Christ’s’ presence and to endure. Slowly, I came to see that every moment of every day we, like Simon, stand under a “hole in the heavens”, if we will only look up. Jesus, before so many significant events, raised his eyes to heaven – before the miracle of the loaves and fishes, before healing the man born deaf and dumb, before raising Lazarus, and before instituting the sacrament of the Eucharist at the Last Supper. My mother’s soul left her in the darkness before dawn four days after Good Friday. I held her in my arms as her powerful heart fought to the last. Then the rasping breath became suddenly quieter. There was a pause between breaths, then a longer pause. Finally, almost imperceptibly, she drew her last breath in this world and I whispered Christ’s final prayer, “Into thy hands I commit her spirit”. Christ’s own words in turn echoed Psalm 31, verse 5 and - almost like a response - the remaining part of that verse suddenly filled my ears, “thou hast redeemed me, O Lord, faithful God”. As I laid her back on the pillow, the dawn chorus broke outside. Birdsong poured though the open window. The sky was still black, night’s density thinning only along the brim of the horizon. This crescent of light would sweep around the earth from pole to pole with the dawn chorus accompanying it as it has for a million years. No matter how deep the night, the continuous movement of light and song is illuminating some part of the world. My mother had reached a dawn without darkness. [1] Jn 19:28,29 [2] Ps 69:3 [3] Romans 10:20: St Paul quoting Isaiah 65:1 [4] St John of the Cross, The Dark Night of the Soul , Bk 11, Ch XVI The great mystic, St Teresa of Avila, said that in the Song of Songs the Lord is teaching the soul how to pray, “Along how many paths, in how many ways, by how many methods you show us love! ...in this Song of Songs (you) teach the soul what to say to you... We can make the Bride’s prayer our own.”

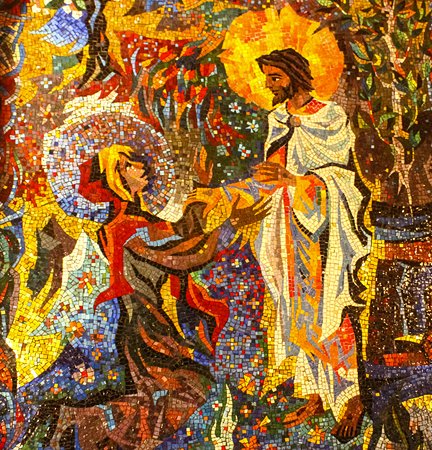

When I first read these words of Teresa’s, I revisited the Song of Solomon and chose a passage at random as a form of prayer: As the apple tree among the trees of the wood, So is my beloved among the sons. I sat down under his shadow with great delight, His fruit was sweet to my taste. He brought me to the banquet hall. His banner over me is love. Strengthen me with raisins, Refresh me with apples; For I am faint with love. His left hand is under my head. His right hand embraces me. My reaction to the experience of praying the Song of Songs was a revelation to me. I have to say it felt completely alien – almost shocking in its loving, desiring, tactile imagery. If Teresa was right and this is the kind of language in which God longs to hear the soul speak, it seemed to me that I had to make a radical shift in my perception of what it is to love and be loved by God. Up to then, I had thought of ecstatic delight in God’s presence as the preserve of mystics, inaccessible to people living among the commonplace realities of everyday life. Prayer as passionate seeking, as desolation in the absence of the beloved, and rapture in finding him - this kind of prayer was utterly outside my experience. It felt unnatural, irreverent. I could not imagine myself experiencing prayer as described by Teresa: “I used unexpectedly to experience a consciousness of the presence of God of such a kind that I could not possibly doubt that he was within me or that I was wholly engulfed in him”. I have often felt like the rich man in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus. When he died, the rich man could see “Abraham, far off” but between Abraham and him a great chasm existed which could not be bridged. In the same way, God can seem very far off – perceived but not experienced. The chasm separating us from him is often the past. Past failures can take unrelenting possession of us. We can become haunted by the memory of bad decisions, missed opportunities, unrealised potential. We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; and we have done those things which we ought not to have done. The sense of steps taken irretrievably in the wrong direction, of having done harm, can be crippling –attaching to our spirit like a leech, draining us of hope and optimism, so that – in Donne’s powerful line - “I am rebegot / Of absence, darkness, death; things which are not”. This terrifying awareness of repeated failure sucks our energies inward. We make half-hearted efforts to move forward, but then think “too little, too late” and retreat into our inadequacy. We dig a hole, put our talent into it, and pile the stifling earth on top. “I was afraid, and I went and hid your talent in the ground” (Mt 25:25). The parable of the ten talents reminds us that nothing can excuse inaction. We must spend our lives with an energy which has nothing to do with what we consider our worth to be. The fact that we may have fallen again and again on our life’s journey does not permit us to pause, let alone stop altogether. The fact that we have failed ourselves and failed others does not excuse us from a continual effort to forgive and love – and that process starts with ourselves. If we cannot accept that we ourselves are forgiven, we cannot forgive others. If we cannot weep for ourselves, how can we “weep with those who weep”? (Romans 12:15). The woman who washed Jesus’ feet, described in Luke 7, breaks upon an uncomfortable scene. Jesus is being entertained at the house of Simon the Pharisee, who has welcomed him with minimal hospitality – indeed, his omission of the common courtesies of the time amounts to a calculated insult. There is no kiss of greeting; no offer is made to wash the dust of the road from a guest’s feet; there is no anointing of the head with oil. “And behold, a woman of the city, who was a sinner, when she learned that he was at table in the Pharisee’s house, brought an alabaster flask of ointment, and standing behind him at his feet, weeping, she began to wet his feet with her tears, and wiped them with the hair of her head, and kissed his feet, and anointed them with the ointment.” It is a marvellous incident. This woman accepted that she had been forgiven. It is likely she has already met Jesus - perhaps she was among the crowd at Capernaum when Jesus said, “All that the Father gives me shall come to me; and the one who comes to me I will certainly not cast out” (John 6:37). It is because she is forgiven that she shows such love to Jesus: “Therefore, I tell you, her sins, which were many, have been forgiven; hence she has shown great love” (Luke 7:47). The significance of this is that accepting that she was forgiven made it possible for the woman to show such love. The woman never speaks; her love and repentance are beyond words. This is the most sensual scene in the New Testament - the erotic overtones of the cascade of hair (in ancient Israel only prostitutes wore their hair loose in public), the perfumed air, the smoothing on of the aromatic ointment, the woman’s lips pressed over and over again on Christ’s bare feet. He accepts her touch as fitting and right; he welcomes her unconscious intimacy – sees beyond her reputation and her behaviour and into her heart. Where Simon sees sex, Jesus sees love. This unspeaking woman is praying with her body and with her heart. It’s a way we seldom pray. Her prayer is part of a tradition as old as the passionate, lyrical and sensuous Song of Songs. God delights in every aspect of his creation – physical as well as spiritual. It was into our bodies that he breathed the spirit of life. It is through our bodies that we make the journey towards him. Over and over in Scripture, his love for his people is expressed in highly tactile imagery – the cradling of an infant in its mother’s arms, the dandling of a toddler on its father’s knee, the love of a bridegroom and a bride. It isn’t difficult to imagine the woman in Simon’s house praying the Song of Songs. “How much better is your love than wine! The fragrance of your perfumes than all manner of spices!” As Teresa of Avila wrote, “it is not a matter of thinking much, but of loving much”. 31/3/2018 0 Comments Easter sundayMosaic from Washington National Cathedral “And when the Sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome, brought spices, so that they might go and anoint him. And very early on the first day of the week they went to the tomb when the sun was risen” (Mk 16, 1-2).

We can picture the women on their sorrowful mission. They move through the garden with heavy hearts, concentrated on the grim task that lies ahead of them, oblivious to all the sights and sounds and smells of the dawning spring morning. They are oblivious, above all, to the glorious presence of the risen Christ not a stone’s throw away from them. Their great concern is how they are going to roll back the heavy stone that seals the tomb - “it was very large” (Mk 16:4). Then they arrive at the tomb to find the stone rolled back, and an angel of the Lord seated upon it: “His appearance was like lightning, and his raiment white as snow” (Mt 28:3). The angels, or angels (Luke and John mention two), are alone in the tomb: there is no body. Only the linen winding cloths remain and, neatly rolled up, the napkin that covered the face. “Why do you seek the living among the dead?” the angels ask. Lord, we too can seek you too often among dead things. Help us to realise - when we are weighed down with sorrow, anxiety or hopelessness - that you are no further from us than you were to the women in that dawn garden. Sadness and pain can blind us to the fact that your healing presence is beside us; can make us deaf to your voice calling us by name. “I have called you by name and you are mine." How I can identify with Mary and the other women! I, too, have heard your words and did not understand. I have seen and did not perceive. I have experienced your redemptive love in my own past and failed to remember it. Wrapped in sorrow, I have passed you in my daily life without recognising you. I have trodden a dark and lonely path oblivious to your glory shining around me. I have made of my life a wasteland of unnecessary worry, when you have already removed the seemingly immovable obstacles that trouble me, rolling them back as effortlessly as you did the huge stone at the garden tomb. 24/3/2018 1 Comment lent: holy week“Your enemies shall come fawning to you; and you shall tread upon their high places” (Deut 33:29). These are the last words of Moses. Because of his sin of unbelief and disobedience at Meribah, Moses is not permitted to lead his people into Canaan. However, immediately before his death, the Lord leads him to the top of Mount Pisgah and shows him the Promised Land. Now Jesus, whom Moses prefigured, is about to mount to a high place and open another Promised Land for all who had been excluded from it by the original sin of Adam. He who will free all enslaved by sin goes to a shameful form of execution reserved for slaves, subversives and criminals. He, whose power transcends any temporal power, is condemned to a death the spectacular cruelty of which is designed to reinforce the notion of the power of the state and the powerlessness of the individual. He will not climb this hill with the ‘hind’s feet’ of the Psalms; this ascent will be a stumbling, painful one. This is the ‘mountain of myrrh and the hill of frankincense’ (Sol 4:6): myrrh for burial, frankincense for embalming. “So they took Jesus, and he went out, bearing his own cross, to the place called the place of a skull, which is called in Hebrew Golgotha” (Jn 19:17). It may have been the crossbeam that Jesus carried, placed across His shoulders and with His arms bound around it; or it may have been the entire cross, laid heavily across one shoulder. Either way, the dragging weight on his torn flesh must impede His progress cruelly. At some point it was feared that, in his weakened state, Jesus might not survive his climb to Calvary. So “…they seized one Simon of Cyrene, who was coming in from the country, and laid on him the cross, to carry it behind Jesus” (Lk 23:26). The cross is laid on Simon against his will; indeed, we may assume that he bitterly resents his humiliating burden. Is Jesus - as so many of the sick, the incapacitated, the dependent - painfully aware of the reluctance with which Simon’s assistance is given? Already stripped of dignity by his suffering, he must be further humiliated by the obvious distaste with which Simon approaches his task. However, it is likely that the quality of Simon’s acceptance transformed the nature of the giving. We do not know whether Simon was Jew or Gentile; but we do know that his sons, Alexander and Rufus, will become sufficiently prominent in the young Christian church to be mentioned by Mark (Mk 15:21). Was Simon’s involuntary sharing of Christ’s suffering, then, a transforming experience? Did he, on accepting Jesus’ yoke, find, after all, that the yoke was easy and the burden light? “If anyone forces you to go one mile”, Jesus urged at the Sermon on the Mount, “go with him two miles.” A cross may be imposed by God. It may not be accepted willingly but if, at the end, it is accepted, then comes the grace for going the extra mile. Lord, how often have I shouldered your cross unwillingly! You have laid it on my shoulders and I have seen only the burden. I have seldom paused to reflect that, if the woman who touched Your garment in a crowd was instantly healed, how much more powerful might be the sharing of your own cross.  The above image, Ivan Kramskoi's Christ in the Desert (1872,Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), powerfully captures - for me anyway - the vulnerability of Jesus in his desert sojourn. Like the Hebrews leaving Egypt, we have to ease off the shackles of slavery to false gods. The false gods are different for each of us – a desire for money, status or power, an addiction, an old resentment or hatred, an extramarital love affair, an obsession with work, a refusal to advance on our journey for fear that we may not be able to complete it – but all have this in common: the false gods displace the real God for us. They drain our energies and our hope. Life with them has no savour; life without them is unimaginable – a wilderness too huge and bare to contemplate. We have become so accustomed to our enslavement that our chains have grown comfortable. We sit by our “fleshpots”; we “eat our bread to the full”. We shrink before the colossal aridity of the desert. Better the devil we know than the one we do not. Even Jesus had to be “driven” into the wilderness, where he fasted for 40 days, as Elijah did before him. Just as he shared our human nature, our birth and growing pains, our loves and terrors, Jesus allowed himself to be tested as we all must be tested. If what is tested in us is our weakest point, then the temptation of Jesus seems to centre on his feelings about his mission. Twice Satan says “If you are the Son of God…” Does this suggest that Jesus himself is not certain about who he is? It is easy to empathise with him if this is so. It is easy to feel disbelief in our own worth and destiny. It is so easy to deny the colossal reality that we are living temples, in which the Word of God is eternally spoken. The wild beasts of Christ’s wilderness haunt our internal landscapes too - beasts of terror, rage and despair. So, we turn to Jesus and see how he coped. “If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become bread,” the devil said. Christ’s reply, “Man shall not live by bread alone” is a direct quotation from Moses in the wilderness, addressing his vacillating followers. (Deut 8:3). It speaks directly to us today – we can starve in the desert of our souls without the word of God to feed us. Satan, bringing Jesus to the pinnacle, invites Jesus to test whether he is, indeed, the One the psalmist wrote about, “For he will command his angels concerning you, to guard you in all your ways. On their hands they will bear you up, so that you will not dash your foot against a stone” (Ps 91:11-12). Again, Jesus quotes Moses, “Do not put the Lord your God to the test.” (Deut 6:16). The striking parallels which Christ draws between his 40 days in the desert and the Israelites’ 40 years in the wilderness are full of significance. Jesus emphasises our dependence on God, and our inability to accelerate our passage to the Promised Land. Satan was offering a quick fix to any doubts Jesus may have had, and Jesus turned it down. There are no short cuts on our journey. The Promised Land was not a 40-year journey from Egypt, but 40 years was what it took to prepare the Israelites to take possession of the Promised Land. In recalling the experience of the 40 years' wandering, there is another subtext. The Israelites faced a massive recurring temptation which we, too, encounter: the desire to say “enough – we’ve tried this and it isn’t working. Let’s turn back”. But they found that God is Lord of the wilderness as well as Lord of the oasis. The only way we can know that is to experience it. It may be a long and a hard journey to the Promised Land, but the only way to get to it is across the desert. The alternative is to stagnate in our own particular Egypts. If we do that, we will never experience transformation in, and transformation of, the desert. By saying, “I can’t go any further”, we will be the earthen vessels striving with the potter, “Woe to you who strive with your Maker, earthen vessels with the potter! Does the clay say to the one who fashions it, ‘What are you making?’ or ‘Your work has no handles?’" (Isa 45:9) The Promised Land is waiting for us to take possession of it – not tomorrow, not in some faraway time when we will have dispensed with all the things that now distract us or anaesthetise us, but now. As God said to Moses on the hills of Moab, within sight of the Promised Land, “This commandment that I am commanding you today is not too hard for you, neither is it too far away. It is not in heaven, that you should say, ‘Who will go up for us to heaven for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?’ Neither is it beyond the sea, that you should say, ‘Who will cross to the other side of the sea for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?’ No, the word is very near to you; it is in your mouth and in your heart for you to observe”. (Deut 30:14) If we have the courage to place ourselves in the hands of our Maker, we will feel the heavens open and rain grace down upon us, transforming our desert: The wilderness and the dry land shall be glad, the desert shall rejoice and blossom; like the crocus it shall blossom abundantly, and rejoice with joy and singing. (Isa 35:1) We will hear the words of Moses to the Israelites as they emerge from the wilderness and understand that: "The eternal God is your refuge, and underneath are the everlasting arms." (Deut 33:27). We will know that angels have ministered to us without our realising it. And, because Christ went through the same experience, we will be able to take comfort in the knowledge that he is both the Way and the Wayfarer.  In the Bible, God communicates with his people in many different ways – most of them very loud! He speaks through a whirlwind in Job, an earthquake in Exodus and Hebrews, a voice like thunder in Samuel. Job, Psalm 104, and John. His address to Ezekiel is preceded by a storm and a “sound of tumult”; in Revelation, thunder and lightening rumble and flash around his throne. In only one place in the Bible does he speak in a “still, small voice”, and that is during his interchange with Elijah in the Judean Desert. When Abraham and Moses entered the desert, it was as part of a journey forward. Elijah, in contrast, was retreating, from the terrifying wrath of his arch enemy, Queen Jezebel. He fled first from the Northern Kingdom to Beersheba, a journey of about 260 miles, and then from Beersheba into the Judean desert. The desert was less a geographical location than a spiritual point in Elijah’s earthly pilgrimage, as it had been for the Israelites 600 years earlier. The true desert – where purification takes place - is not outside us, but within. Like a physical desert, our internal wilderness can be a place where we feel terrifyingly alone and in which we want to spend as little time as possible. Yet, it is only in this - at best inhospitable and at worst dangerous - place that we can encounter God. Even Jesus, the “new Elijah”, had to enter the desert – “driven” by the Spirit. This is a place in which we can be tempted by indifference, by lethargy, by fear, by despair, by self-doubt – “I can’t do this thing”. The Elijah of 1 Kings, Chapter 18 is a formidable man, standing alone on Mount Carmel against 450 prophets of Baal and a hostile king. He puts the prophets of Baal to the test, challenging them to bring fire to the earth through their prayers to Baal, and then himself successfully calling down fire and then water from heaven. He does not doubt for a moment that God will respond to his call. He triumphs over the false prophets and cows the sinister king, who goes back to his wife, Jezebel, and tells her all that Elijah had done. This rekindles her anger and she vows to have Elijah’s life. Having provided such spectacular proof that Yahweh is indeed God, Elijah confidently expected that the apostate Israelites would return to the true path. It didn’t happen. The only communication after the triumph on Mount Carmel was Jezebel’s death threat. It is astonishing to see how quickly terror takes over this towering Old Testament figure. Despite the many proofs he has had of God’s power and support, he runs for his life from an angry woman. By the time he enters the desert, he has given up all hope, and all faith in his mission. At the end of a day’s journey, he cries out in fear and exhaustion, “I have had enough, Lord. Take my life; I am no better than my ancestors.” Elijah is saying “I am not the person you think I am, Lord. I can’t do these things you ask of me. Don’t ask me to do any more.” Fear has given way to something more insidious, the state of acedia - described by Aquinas as “the sorrow of the world that wreaks spiritual death”, and by St John Cassian as the “noonday demon”. It is so easy to identify with Elijah here. Times of immense faith can evaporate in seconds, giving way to torpor and listlessness. Instead of living, we exist. And yet, there is much hope in this grim episode in the story of Elijah. In the loneliness of the desert, an angel comes to bring three nights of sound sleep and good sustenance. Then, refreshed, Elijah journeys 40 days and 40 nights to Mount Horeb, where in the silence of the desert, after the wind and the fire and the earthquake have passed, he is able to hear God’s “still, small voice” which gently asks him “Why are you here, Elijah?” Twice he asks, and twice Elijah is allowed to get all his grievances off his chest ““I have been very zealous for the Lord God Almighty. The Israelites have rejected your covenant, torn down your altars, and put your prophets to death with the sword. I am the only one left, and now they are trying to kill me too.” And then God sends him back the way he came, to achieve more and greater works than any he had done so far. I take comfort from this story of the weakness of the greatest of all the Old Testament prophets – the prophet who appeared along with Moses at the Transfiguration. Elijah, struck with paralysing discouragement, had to go into a lonely, silent desert and there unburden himself to the Lord of all his frustrations and fears. In that seemingly arid and unpromising place, he drew new strength and was able to answer the question, “Why are you here?” – not with words, but by embarking on a new journey over old terrain: “Go back the way you came”. I am reminded of TS Eliot’s lines from “Four Quartets”: “We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time.” The Desert of Zin in the Negev The journey of Moses took 40 years. It seems to have been a much more tedious journey than that of Abraham, and it is very easy to empathise with Moses’ “murmuring” travelling companions. The Hebrews left Egypt in a blaze of glory. Their years under a cruel oppressor ended with the first Passover, and they crossed the Red Sea on dry land. Their “song of the sea” in Exodus 15 rings with joy and confidence in a delivering God. But, by the time the Hebrews reached the Wilderness of Zin, they had had enough of desert privations. They wanted to return to slavery in Egypt, saying bitterly to Moses and Aaron, "If only we had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the fleshpots and ate our fill of bread; for you have brought us out into this wilderness to kill this whole assembly with hunger." (Ex 16:3)

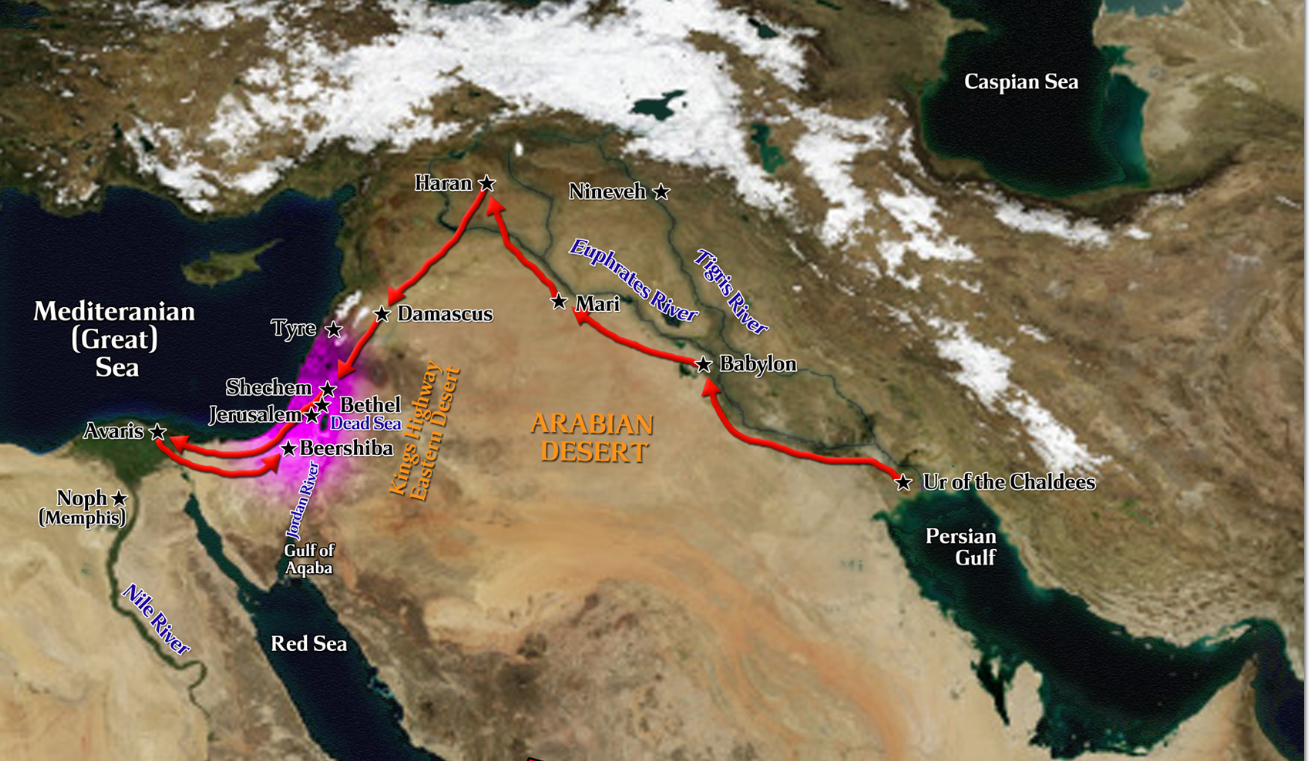

The miseries of slavery had been forgotten. The past was now viewed selectively and seemed a lot safer and more secure. In contrast, the future they faced with Moses was unknown and comfortless. The Hebrews wanted to reverse their journey. As I have often done. I have often dabbled in the wilderness and then rushed back to the known comfort zones of my own Egypt. How often have I started Lent, for example, with a determination to advance on my journey! How often have I resolutely put behind me the many obstacles to my spiritual progress only to lose heart at the first hurdle! Like Pharaoh’s chariots, my wheels were clogged “so that they turned with difficulty” (Ex 14:25). When the vastness of the wilderness opened up before me, slavery suddenly seemed a lot more attractive. Despite their yearnings for Egypt’s fleshpots, in Exodus 17:1 we read “From the Wilderness of Zin the whole congregation of the Israelites journeyed by stages, as the Lord commanded”. There is no standing still – God asks us to keep moving. As the Hebrews did – but in the next breath we are told that they began to quarrel with Moses again. There was no water to drink, so they asked Moses “Why did you bring us out of Egypt, to kill us and our children and livestock with thirst...Is the Lord among us or not?” Again, the Lord provides, but by the time they reach Rephidim the Hebrews are quarrelling again. So it goes on throughout the Exodus journey – a rollercoaster of ups and downs, of enthusiasm and grumbling, of devotion to God, and worshipping a golden calf. Amid all this, we have the giving of the Ten Commandments, the Ark of the Covenant, the revelation of God’s name and the renewal of God’s covenant with his people. Even within sight of the Promised Land, the people lost heart. The spies they sent to reconnoitre the land came back with reports of a gigantic and powerful people – “to ourselves we seemed like grasshoppers, and so we seemed to them” (Numbers 13:33). The old refrain went up, “Would that we had died in the land of Egypt! Or would that we had died in this wilderness! Why is the Lord bringing us into this land to fall by the sword? Our wives and our little ones will become booty; would it not be better for us to go back to Egypt?” (Num 14: 2-3). Only Caleb and Joshua remonstrated with the people. In anger, God prolonged their sojourn in the wilderness so that none of those alive at that time, with the exception of Caleb and Joshua, would cross into Canaan. The 40 years wandering seems pointless until one realises what was achieved in that time. The people Moses led out of Egypt had been enslaved for four centuries. The Hebrew tribes of Israel entered Egypt voluntarily, probably about 1600 B.C., at the invitation of Jacob’s son Joseph, then a high official in Pharaoh’s administration. They initially prospered, and their numbers multiplied over three centuries. However, “Now a new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph” (Ex 1:8). Under his rule, Hebrews were disenfranchised and forced into slave labour in Egypt’s massive building programme, and in the noxious conditions of the turquoise mines. Their spirit was utterly broken after centuries of bondage. The mixed multitude which set out from Egypt was in no condition to take possession of the land promised to it. In the wilderness years, Moses brought God’s law to the people and welded them together in disciplined monotheism. These “stiff-necked” and vacillating people have been a source of immense encouragement to me: however often they stumbled and longed to turn back, they nonetheless kept moving – urged relentlessly forward by God. They must have longed to stay longer at each oasis – especially at the large oasis of Kadesh Barnea between the deserts of Zin, Shur and Paran where they camped for many years. But, in their subsequent wanderings, the Hebrews were transformed. The murmuring mob became a great nation and the covenant made with Abraham was fulfilled. The Biblical desert is a place of passage and purification. In the desert landscapes of our souls we must learn that God is with us at every stage of the journey. He is God of the wilderness as well as God of the land flowing with milk and honey. However, to reach the latter, we must traverse the former. We, too, need to cast off our inertia and our false gods if we are to enter into the Promised Land. 19/2/2018 3 Comments lent week one: "so abram went". I recently came across an article from the New York Times of 13 March 1983, “In the Steps of Abraham”. It began: “The heavy curtains of far-distant time part upon an unlikely stage whose name is Ur. Today, Ur is a desert scrubland with miserable ruins jutting from terrain of sand and mud. It is about 120 miles northwest of the Persian Gulf, in the country we now call Iraq. Unlikely or not, however, very nearly 40 centuries ago, here began a journey that transcended history, and whose arc etched a crescent of hope and faith so indelibly that it determined the motive and course of events for centuries down to this day and far beyond the borders of the nations that were in its path - places we know as Iraq, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Egypt, Jordan.” Ths journey began with a call from God: “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation” (Gen 12:1-2). God’s call is met with many different responses in the Bible. A frequent reaction is reluctance – usually based on a sense of inability to carry out God’s mission. Moses cries out “Who am I, that I should go unto Pharaoh, and that I should bring forth the children of Israel out of Egypt?" (Exodus 3:11). Gideon, called upon to deliver the Israelites from bondage to their Midianite overlords, responds “Pray, Lord, how can I deliver Israel? Behold, my clan is the weakest in Manasseh, and I am the least in my family” (Judges 6:15). Jeremiah pleads youth: “Ah, Lord God! Behold I do not know how to speak, for I am only a youth” (Jer 1:4). With Jonah, actions speak louder than words as, hearing God’s call to go to Nineveh, he promptly takes a ship sailing in to Tarshish, believed to be in southwestern Spain – about as far from Nineveh as anyone could get in the ancient world! Abraham could well have pleaded old age. He was 75 years old and probably looking forward to a tranquil end to his days, when he received the call. He had had more than his share of travelling up to this point. His childhood was in Ur of the Chaldees in what is now south Iraq but, when he was still a boy, his family moved to Haran, in what is now Turkey – a journey of over 600 miles. That journey, while long, was tolerable – following established and well-policed trade routes along the course of the river Euphrates. Now he was being called into utterly uncharted territory. St Paul recognises the magnitude of the challenge: “By faith Abraham, when called to go to a place he would later receive as his inheritance, obeyed and went, even though he did not know where he was going" (Hebrews 11:8). “So Abram went”. As Mary, daughter of Abraham in flesh as well as in faith, will answer “yes” to the divine call two thousand years later, Abraham responded to God’s command. It is an extraordinary acceptance. While he was a monotheist in a polytheistic society (we know from Joshua 24:2 that his own father worshipped idols), Abraham knew far less about God than did Moses, Jeremiah or Jonas. No miracles, no signs accompanied the call; just a promise to this childless man which must have seemed unbelievable. He simply obeyed. We know that he experienced terror on his journey – the opening line of Gen 15 has the Lord saying to him, “Fear not, Abram, I am your shield”. And, again. “As the sun was going down, a deep sleep fell on Abram; and lo, a dread and great darkness fell upon him” (Gen 15:17). He left Haran in southern Mesopotamia (now in modern Turkey) and travelled south-west across Syria and through Damascus. He probably followed the ancient trading route, the “King’s Highway”, from Damascus along the hilly backbone of Jordan and into Canaan. He crossed though Shechem (today the Palestinian town of Nablus) and Bethel; then south to the Judean desert where famine forced him south-west to Egypt and the fertile Nile Delta. After a sojourn in Egypt he retraced his steps through the Judean desert to Canaan, eventually dying at Hebron (where his descendant, David, would be anointed king nearly a thousand years later). The 1,500-mile journey (3,200 miles if one includes the route from Ur to Haran) had no obvious geographic conclusion. However, in the course of it, Abraham found the land which God promised to his descendants; his covenant with God was established; his long-abandoned hopes of a child by Sarah, his wife, were realised; and his name was changed from Abram to Abraham, “the ancestor of a multitude of nations” (Gen 17:5), the spiritual father of the world’s Christians, Jews and Muslims - half of the people alive on earth today. So this is not simply a geographic journey. Abraham could not grow spiritually while he remained comfortably settled in an idolatrous society, never moving out of his comfort zone. Pope St John Paul II, in a homily given on Wednesday, 23 February 2000, asked: "Are we talking about the route taken by one of the many migrations typical of an era when sheep-rearing was a basic form of economic life? Probably. Surely though, it was not only this. In Abraham's life, which marks the beginning of salvation history, we can already perceive another meaning of the call and the promise. The land to which human beings, guided by the voice of God, are moving, does not belong exclusively to the geography of this world. Abraham, the believer who accepts God's invitation, is someone heading towards a promised land that is not of this world." This Lent is an opportunity to leave our own comfort zones, and put behind us the many obstacles to our own spiritual journey. In a noisy world, we can try to be still enough to hear God's voice; and be courageous enough to act on it. Which evokes another quotation from Pope John Paul II: "Have no fear of moving into the unknown. Simply step out fearlessly knowing that I am with you, therefore no harm can befall you; all is very, very well. Do this in complete faith and confidence." 10/2/2018 8 Comments Ash wednesday: into the wilderness“And behold, thou wert within me, and I out of myself, where I made search for thee!” (St Augustine).

This Lent, I am heading for the Judean Desert. Not in body (although I would dearly love to), but in spirit. I have long been fascinated by the unescapable presence of the wilderness in the Old and New Testaments, permeating the Bible as vividly as do any of the Biblical characters. It is always there, its vastness and barrenness a stone’s throw from the habitable world. 'Wilderness' in the Bible refers mainly to two distinct locations: the Sinai Desert, where the Hebrews wandered for 40 years after the exodus from Egypt, and the relatively bare, uncultivated area in the south of the Promised Land known as the Negeb, or Judean Desert. The desert is a place of contradictions – stark, barren, and terrifying. “The great and terrible wilderness” is both a place of trial and of deliverance, of purgation and illumination. Abraham passed through the desert at least twice on his immense migratory journey. This is the place where the wanderings of Moses and his people culminated in the birth of Israel as a nation; here David found refuge from Saul; here the Essenes escaped Hellenistic domination of Jerusalem; here the Zealots made their final, desperate last stand at Masada against the might of Rome; and here John the Baptist prepared for his mission. In the desert Elijah, deeply discouraged, longed for death - but it was here that God came to him in the still, small voice. This is the place where the original scapegoat was sent (Levit 16:10), carrying the sins of the people on his back; and it was to the desert that Jesus – who carried all our sins - was driven by the Spirit. One of Christ’s paradoxical sayings is that we have to lose our life to save it. Equally, we have to go where there are no paths in order to find our direction.The wilderness, or desert, is the ultimate trackless zone. In the Bible it is a place of transformation and revelation. This “howling wilderness waste” (Deut 32:10), swept by deadly winds (Is 21:1; Jer 4:11), is at the same time a holy place, where the glory of God descended upon Moses “like a devouring fire” (Ex 24:17). Passage through the wilderness was an integral part of their mission for Abraham, Moses, John and Jesus. But where is such a place to be found in a modern suburban life? In our frenetic, noisy, peopled world, where are we to find these great stark tracts of silence and isolation, these testing grounds with their lurking dangers of heat and thirst and wild beasts? Where are we to find a place where we strip away everything that is superfluous, everything that distracts us or deadens us, and place ourselves utterly in God’s hands? To find the answer, I plan to retrace the desert journey – sometimes with Abraham, Moses and John – but especially with Jesus, since it is above all in his life that we seek the meaning of our own. The more I read the Biblical accounts, the clearer it became that the journey is metaphorical as well as literal. The wilderness exists on maps, but it also exists within us. For many of us, our “selves” are like haunted houses – tenanted with the ghosts of past loves and losses, triumphs and disappointments, achievements and failures. Sorrows and rage as old as infancy can lurk within us and the accumulation of a lifetime’s shortcomings can make our “selves” uncomfortable and unwelcoming places in which to be, so that we try to spend as much time as possible outside ourselves. We fill our days with noise and activity; sometimes we deaden our pain with alcohol, food, work, sex or drugs. An Episcopal monk and spiritual writer, Martin L Smith, describes our habitual condition as one of being under an anaesthetic: “Most of us have a primary defence mechanism against being overwhelmed by the pain of the world and our own pain. It is as if we administer to ourselves an anaesthetic to numb its impact. The price we pay is that it also numbs our capacity for joy, but until we surrender to the Spirit of God we reckon the price to be worth it.” (Martin M Smith, A Season for the Spirit, London 1991, p.21). Extreme youth or extreme age does not excuse us from making the journey into the wilderness. John the Baptist appears to have entered the desert at a very young age, in preparation for his mission as the Forerunner. Abraham – then known as Abram - was 75 years old when he received that irresistible call “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you” (Gen 12:1). It is almost never too late to make this journey, although the longer we leave it the harder it becomes. Our distractions, addictions or avoidances grow like tumours around vital organs. If we leave the tumours untreated, we die. The longer we wait to remove them, the more potentially deadly the operation. If we don’t confront the wilderness inside, we can never overcome our own isolation. If we don’t sufficiently accept and love ourselves, we can never really enter into communion with others and with God. Was this what St Augustine was getting at when he cried “And behold, thou wert within me, and I out of myself, where I made search for thee!” Next week: Travelling with Abraham |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed