|

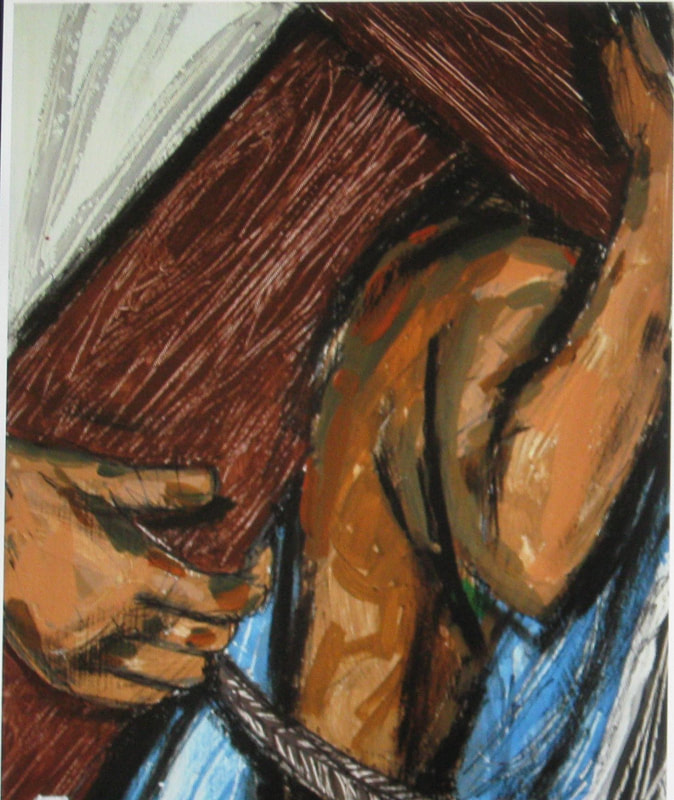

11/11/2018 1 Comment A Deathbed encounterSimon of Cyrene Helps Carry the Cross of Jesus. Painted by Ken Cooke. Courtesy of Church of St George the Martyr, Wash, Newbury, UK. I met Simon of Cyrene at my mother's deathbed, where I had been keeping a vigil for many long days. I remember the rain, the dark, the quiet. The open window and the rain falling like comfort. I listened to her breathing and watched her – the skeletal body with the powerful heart, the heart that would not let her die. Her hand, so beautiful still, lay on the smooth cover of the bed. My mother could no longer swallow. I had a supply of small sponges which I used to moisten her parched lips. In that sickroom, the shadow of Calvary cast such a deep shadow that the resonance of the gesture was inescapable, “they put a sponge full of vinegar on a branch of hyssop and held it to his mouth”.[1] Another, even older voice, sounded in my ears, “I am worn out calling for help; my throat is parched. My eyes fail, looking for my God.” [2] Three times before she sank into the final coma, she whispered “My God, my God, why abandonest thou me?” My mother had been a beautiful, energetic and gregarious woman, with many interests. She was a daily Mass-goer throughout her long life and really lived her faith. Her house and her heart were always open to anyone in need, and she radiated encouragement and hope. It was only in her later years that I came to know that the hope she gave to others was not often something she experienced herself. Yet there very few among her large circle of friends who suspected how much her faith was a willed thing and not a gift from God. As she approached the end of her life, she became possessed by an unrelenting terror of death which increased dramatically in her final illness. “My God, my God, why abandonest thou me?” The archaic language was that of her childhood. When she reached for a concept of God, it was the God of her far-off schooldays – an Old Testament God of judgement and retribution. Her religion, practised so faithfully over so many years, brought her no solace. No glimmer of comfort could touch her. In that small room, I watched her world contract. Terror filled her mind to the exclusion of almost any other emotion. Yet, when I would arrive in her room, she never failed to recognise me. Her eyes became a blazing glory of love. All her former strength and hope lived once more in that shining gaze. Then the darkness took hold of her again. And of me. Together, we took her cross up again. It was there, in that quiet room, that I gazed across the space of two millennia and saw him, another person bent under a cross not his own. Another person on a seemingly hopeless journey. Simon of Cyrene. Cyrene was an ancient Greek colony, beautifully set in a fertile valley beneath the wooded uplands of Jebel Akhdar in what is now north east Libya. The 7th Century BC Greeks who settled Cyrenaica, fleeing drought in their home island of Thera, were directed to this spot by Berber tribesmen who told them that there was a “hole in the heavens” here. Through this “hole” abundant and life-giving rain fell to create a lush expanse in the wastes of the Sahara. Pressed into service by the flat of a Roman spear, we can be sure that Simon of Cyrene did not welcome his arduous and humiliating task. Yet at this moment in time, all unknowing, Simon – like the founders of his native city seven centuries earlier - is standing under “a hole in the heavens”. The blood and sweat which rain down on him will transform his life. One would have expected Simon to put the memory of his horrible experience behind him as quickly as possible, but his two sons, Alexander and Rufus, will become sufficiently prominent in the young Christian church to be mentioned by Mark and Paul ((Mk 15:21; Romans 16:13). In shouldering his burden, it seems that Simon discovered that sometimes it is enough just to be in Christ’s presence, “I was found by those who did not seek me. I have shown myself to those who did not ask for me.” [3] Just at this point of Simon’s journey, however, there can be no glimpse of what is to come. The journey from Jerusalem to Calvary begins and ends in darkness. The suffering is unmitigated, the sadness unrelieved. Christ’s own words from the cross seem to be a cry of despair. “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” As I sat with my mother though those pitiless days, I longed for some hint of deliverance, some faint intimation of the Easter that lay beyond Good Friday. I longed for it for myself as well as for her. I couldn’t bear to see her go into unrelieved darkness. There was no evident light for my mother on her last journey. No light for Simon of Cyrene. No light for Christ as he struggles to his place of execution. But the hill of Calvary is also an altar. The victim is also the priest: his death is simultaneously sacrificial and redemptive. When all seems lost, Christ can still say to the crucified thief “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise”. I sat by my mother as Simon probably stood at the foot of the Cross. Simon can have no reason to believe that he is seeing things any way other than they actually are. He is looking at a crucified man, hearing his cry of despair. He watches him die, with no alleviation of his suffering. He watches the breath go out of the crucified man and probably asks himself, as I was asking myself, “what was it all for?” I kept thinking about the dim figures of Alexander and Rufus. If they had become committed Christians it must have been as a result of their father’s brief encounter with Christ on that Good Friday. And I, who had encountered Christ countless times in the Eucharist, could sit by my mother on her Good Friday and not see any Easter Sunday beyond. I listen again with Simon to that terrible cry from the Cross, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” This time I listen somewhat differently. I place Good Friday in the context of Easter Sunday and I place Christ’s words in the context in which they were written. They are the opening words of Psalm 22, and any devout Jew at the foot of the Cross would have known how the Psalm continued. It goes on to describe in graphic detail the nature of the death the Messiah will undergo, and it ends with the ringing proclamation, “Posterity shall serve him; men shall tell of the Lord to the coming generation and proclaim his deliverance to a people yet unborn.” Far from being a cry of despair, it is a shout of triumph. Like Simon, I was present under a “hole in the heavens” without knowing it. What was falling into that room wasn’t the rain which fell onto the desert in ancient Cyrenaica, nor the sweat and blood of Christ which fell upon Simon of Cyrene, but something as fruitful and redemptive as either. It was what John of the Cross described as the dark waters close to God in which the striving soul is hidden and protected, “The soul, though in darkness, travels securely because of the courage it acquires as soon as it enters the dark, painful and gloomy waters of God. Though it is dark, still it is water, and it can only refresh and strengthen the soul in all that is most necessary for it, though it does so painfully and in darkness…Thus the soul goes forth out of itself, away from all created things to the sweet and delightful union of the love of God, in darkness and in safety”.[4] In that room, over those weeks, I came to realise that what we feel is not always important. I prayed for the grace to place myself in Christ’s’ presence and to endure. Slowly, I came to see that every moment of every day we, like Simon, stand under a “hole in the heavens”, if we will only look up. Jesus, before so many significant events, raised his eyes to heaven – before the miracle of the loaves and fishes, before healing the man born deaf and dumb, before raising Lazarus, and before instituting the sacrament of the Eucharist at the Last Supper. My mother’s soul left her in the darkness before dawn four days after Good Friday. I held her in my arms as her powerful heart fought to the last. Then the rasping breath became suddenly quieter. There was a pause between breaths, then a longer pause. Finally, almost imperceptibly, she drew her last breath in this world and I whispered Christ’s final prayer, “Into thy hands I commit her spirit”. Christ’s own words in turn echoed Psalm 31, verse 5 and - almost like a response - the remaining part of that verse suddenly filled my ears, “thou hast redeemed me, O Lord, faithful God”. As I laid her back on the pillow, the dawn chorus broke outside. Birdsong poured though the open window. The sky was still black, night’s density thinning only along the brim of the horizon. This crescent of light would sweep around the earth from pole to pole with the dawn chorus accompanying it as it has for a million years. No matter how deep the night, the continuous movement of light and song is illuminating some part of the world. My mother had reached a dawn without darkness. [1] Jn 19:28,29 [2] Ps 69:3 [3] Romans 10:20: St Paul quoting Isaiah 65:1 [4] St John of the Cross, The Dark Night of the Soul , Bk 11, Ch XVI

1 Comment

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed