|

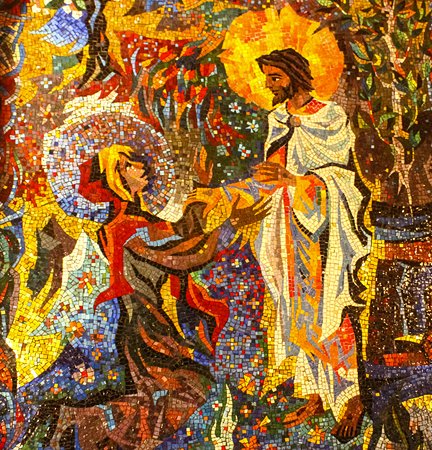

31/3/2018 0 Comments Easter sundayMosaic from Washington National Cathedral “And when the Sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome, brought spices, so that they might go and anoint him. And very early on the first day of the week they went to the tomb when the sun was risen” (Mk 16, 1-2).

We can picture the women on their sorrowful mission. They move through the garden with heavy hearts, concentrated on the grim task that lies ahead of them, oblivious to all the sights and sounds and smells of the dawning spring morning. They are oblivious, above all, to the glorious presence of the risen Christ not a stone’s throw away from them. Their great concern is how they are going to roll back the heavy stone that seals the tomb - “it was very large” (Mk 16:4). Then they arrive at the tomb to find the stone rolled back, and an angel of the Lord seated upon it: “His appearance was like lightning, and his raiment white as snow” (Mt 28:3). The angels, or angels (Luke and John mention two), are alone in the tomb: there is no body. Only the linen winding cloths remain and, neatly rolled up, the napkin that covered the face. “Why do you seek the living among the dead?” the angels ask. Lord, we too can seek you too often among dead things. Help us to realise - when we are weighed down with sorrow, anxiety or hopelessness - that you are no further from us than you were to the women in that dawn garden. Sadness and pain can blind us to the fact that your healing presence is beside us; can make us deaf to your voice calling us by name. “I have called you by name and you are mine." How I can identify with Mary and the other women! I, too, have heard your words and did not understand. I have seen and did not perceive. I have experienced your redemptive love in my own past and failed to remember it. Wrapped in sorrow, I have passed you in my daily life without recognising you. I have trodden a dark and lonely path oblivious to your glory shining around me. I have made of my life a wasteland of unnecessary worry, when you have already removed the seemingly immovable obstacles that trouble me, rolling them back as effortlessly as you did the huge stone at the garden tomb.

0 Comments

24/3/2018 1 Comment lent: holy week“Your enemies shall come fawning to you; and you shall tread upon their high places” (Deut 33:29). These are the last words of Moses. Because of his sin of unbelief and disobedience at Meribah, Moses is not permitted to lead his people into Canaan. However, immediately before his death, the Lord leads him to the top of Mount Pisgah and shows him the Promised Land. Now Jesus, whom Moses prefigured, is about to mount to a high place and open another Promised Land for all who had been excluded from it by the original sin of Adam. He who will free all enslaved by sin goes to a shameful form of execution reserved for slaves, subversives and criminals. He, whose power transcends any temporal power, is condemned to a death the spectacular cruelty of which is designed to reinforce the notion of the power of the state and the powerlessness of the individual. He will not climb this hill with the ‘hind’s feet’ of the Psalms; this ascent will be a stumbling, painful one. This is the ‘mountain of myrrh and the hill of frankincense’ (Sol 4:6): myrrh for burial, frankincense for embalming. “So they took Jesus, and he went out, bearing his own cross, to the place called the place of a skull, which is called in Hebrew Golgotha” (Jn 19:17). It may have been the crossbeam that Jesus carried, placed across His shoulders and with His arms bound around it; or it may have been the entire cross, laid heavily across one shoulder. Either way, the dragging weight on his torn flesh must impede His progress cruelly. At some point it was feared that, in his weakened state, Jesus might not survive his climb to Calvary. So “…they seized one Simon of Cyrene, who was coming in from the country, and laid on him the cross, to carry it behind Jesus” (Lk 23:26). The cross is laid on Simon against his will; indeed, we may assume that he bitterly resents his humiliating burden. Is Jesus - as so many of the sick, the incapacitated, the dependent - painfully aware of the reluctance with which Simon’s assistance is given? Already stripped of dignity by his suffering, he must be further humiliated by the obvious distaste with which Simon approaches his task. However, it is likely that the quality of Simon’s acceptance transformed the nature of the giving. We do not know whether Simon was Jew or Gentile; but we do know that his sons, Alexander and Rufus, will become sufficiently prominent in the young Christian church to be mentioned by Mark (Mk 15:21). Was Simon’s involuntary sharing of Christ’s suffering, then, a transforming experience? Did he, on accepting Jesus’ yoke, find, after all, that the yoke was easy and the burden light? “If anyone forces you to go one mile”, Jesus urged at the Sermon on the Mount, “go with him two miles.” A cross may be imposed by God. It may not be accepted willingly but if, at the end, it is accepted, then comes the grace for going the extra mile. Lord, how often have I shouldered your cross unwillingly! You have laid it on my shoulders and I have seen only the burden. I have seldom paused to reflect that, if the woman who touched Your garment in a crowd was instantly healed, how much more powerful might be the sharing of your own cross.  The above image, Ivan Kramskoi's Christ in the Desert (1872,Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), powerfully captures - for me anyway - the vulnerability of Jesus in his desert sojourn. Like the Hebrews leaving Egypt, we have to ease off the shackles of slavery to false gods. The false gods are different for each of us – a desire for money, status or power, an addiction, an old resentment or hatred, an extramarital love affair, an obsession with work, a refusal to advance on our journey for fear that we may not be able to complete it – but all have this in common: the false gods displace the real God for us. They drain our energies and our hope. Life with them has no savour; life without them is unimaginable – a wilderness too huge and bare to contemplate. We have become so accustomed to our enslavement that our chains have grown comfortable. We sit by our “fleshpots”; we “eat our bread to the full”. We shrink before the colossal aridity of the desert. Better the devil we know than the one we do not. Even Jesus had to be “driven” into the wilderness, where he fasted for 40 days, as Elijah did before him. Just as he shared our human nature, our birth and growing pains, our loves and terrors, Jesus allowed himself to be tested as we all must be tested. If what is tested in us is our weakest point, then the temptation of Jesus seems to centre on his feelings about his mission. Twice Satan says “If you are the Son of God…” Does this suggest that Jesus himself is not certain about who he is? It is easy to empathise with him if this is so. It is easy to feel disbelief in our own worth and destiny. It is so easy to deny the colossal reality that we are living temples, in which the Word of God is eternally spoken. The wild beasts of Christ’s wilderness haunt our internal landscapes too - beasts of terror, rage and despair. So, we turn to Jesus and see how he coped. “If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become bread,” the devil said. Christ’s reply, “Man shall not live by bread alone” is a direct quotation from Moses in the wilderness, addressing his vacillating followers. (Deut 8:3). It speaks directly to us today – we can starve in the desert of our souls without the word of God to feed us. Satan, bringing Jesus to the pinnacle, invites Jesus to test whether he is, indeed, the One the psalmist wrote about, “For he will command his angels concerning you, to guard you in all your ways. On their hands they will bear you up, so that you will not dash your foot against a stone” (Ps 91:11-12). Again, Jesus quotes Moses, “Do not put the Lord your God to the test.” (Deut 6:16). The striking parallels which Christ draws between his 40 days in the desert and the Israelites’ 40 years in the wilderness are full of significance. Jesus emphasises our dependence on God, and our inability to accelerate our passage to the Promised Land. Satan was offering a quick fix to any doubts Jesus may have had, and Jesus turned it down. There are no short cuts on our journey. The Promised Land was not a 40-year journey from Egypt, but 40 years was what it took to prepare the Israelites to take possession of the Promised Land. In recalling the experience of the 40 years' wandering, there is another subtext. The Israelites faced a massive recurring temptation which we, too, encounter: the desire to say “enough – we’ve tried this and it isn’t working. Let’s turn back”. But they found that God is Lord of the wilderness as well as Lord of the oasis. The only way we can know that is to experience it. It may be a long and a hard journey to the Promised Land, but the only way to get to it is across the desert. The alternative is to stagnate in our own particular Egypts. If we do that, we will never experience transformation in, and transformation of, the desert. By saying, “I can’t go any further”, we will be the earthen vessels striving with the potter, “Woe to you who strive with your Maker, earthen vessels with the potter! Does the clay say to the one who fashions it, ‘What are you making?’ or ‘Your work has no handles?’" (Isa 45:9) The Promised Land is waiting for us to take possession of it – not tomorrow, not in some faraway time when we will have dispensed with all the things that now distract us or anaesthetise us, but now. As God said to Moses on the hills of Moab, within sight of the Promised Land, “This commandment that I am commanding you today is not too hard for you, neither is it too far away. It is not in heaven, that you should say, ‘Who will go up for us to heaven for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?’ Neither is it beyond the sea, that you should say, ‘Who will cross to the other side of the sea for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?’ No, the word is very near to you; it is in your mouth and in your heart for you to observe”. (Deut 30:14) If we have the courage to place ourselves in the hands of our Maker, we will feel the heavens open and rain grace down upon us, transforming our desert: The wilderness and the dry land shall be glad, the desert shall rejoice and blossom; like the crocus it shall blossom abundantly, and rejoice with joy and singing. (Isa 35:1) We will hear the words of Moses to the Israelites as they emerge from the wilderness and understand that: "The eternal God is your refuge, and underneath are the everlasting arms." (Deut 33:27). We will know that angels have ministered to us without our realising it. And, because Christ went through the same experience, we will be able to take comfort in the knowledge that he is both the Way and the Wayfarer.  In the Bible, God communicates with his people in many different ways – most of them very loud! He speaks through a whirlwind in Job, an earthquake in Exodus and Hebrews, a voice like thunder in Samuel. Job, Psalm 104, and John. His address to Ezekiel is preceded by a storm and a “sound of tumult”; in Revelation, thunder and lightening rumble and flash around his throne. In only one place in the Bible does he speak in a “still, small voice”, and that is during his interchange with Elijah in the Judean Desert. When Abraham and Moses entered the desert, it was as part of a journey forward. Elijah, in contrast, was retreating, from the terrifying wrath of his arch enemy, Queen Jezebel. He fled first from the Northern Kingdom to Beersheba, a journey of about 260 miles, and then from Beersheba into the Judean desert. The desert was less a geographical location than a spiritual point in Elijah’s earthly pilgrimage, as it had been for the Israelites 600 years earlier. The true desert – where purification takes place - is not outside us, but within. Like a physical desert, our internal wilderness can be a place where we feel terrifyingly alone and in which we want to spend as little time as possible. Yet, it is only in this - at best inhospitable and at worst dangerous - place that we can encounter God. Even Jesus, the “new Elijah”, had to enter the desert – “driven” by the Spirit. This is a place in which we can be tempted by indifference, by lethargy, by fear, by despair, by self-doubt – “I can’t do this thing”. The Elijah of 1 Kings, Chapter 18 is a formidable man, standing alone on Mount Carmel against 450 prophets of Baal and a hostile king. He puts the prophets of Baal to the test, challenging them to bring fire to the earth through their prayers to Baal, and then himself successfully calling down fire and then water from heaven. He does not doubt for a moment that God will respond to his call. He triumphs over the false prophets and cows the sinister king, who goes back to his wife, Jezebel, and tells her all that Elijah had done. This rekindles her anger and she vows to have Elijah’s life. Having provided such spectacular proof that Yahweh is indeed God, Elijah confidently expected that the apostate Israelites would return to the true path. It didn’t happen. The only communication after the triumph on Mount Carmel was Jezebel’s death threat. It is astonishing to see how quickly terror takes over this towering Old Testament figure. Despite the many proofs he has had of God’s power and support, he runs for his life from an angry woman. By the time he enters the desert, he has given up all hope, and all faith in his mission. At the end of a day’s journey, he cries out in fear and exhaustion, “I have had enough, Lord. Take my life; I am no better than my ancestors.” Elijah is saying “I am not the person you think I am, Lord. I can’t do these things you ask of me. Don’t ask me to do any more.” Fear has given way to something more insidious, the state of acedia - described by Aquinas as “the sorrow of the world that wreaks spiritual death”, and by St John Cassian as the “noonday demon”. It is so easy to identify with Elijah here. Times of immense faith can evaporate in seconds, giving way to torpor and listlessness. Instead of living, we exist. And yet, there is much hope in this grim episode in the story of Elijah. In the loneliness of the desert, an angel comes to bring three nights of sound sleep and good sustenance. Then, refreshed, Elijah journeys 40 days and 40 nights to Mount Horeb, where in the silence of the desert, after the wind and the fire and the earthquake have passed, he is able to hear God’s “still, small voice” which gently asks him “Why are you here, Elijah?” Twice he asks, and twice Elijah is allowed to get all his grievances off his chest ““I have been very zealous for the Lord God Almighty. The Israelites have rejected your covenant, torn down your altars, and put your prophets to death with the sword. I am the only one left, and now they are trying to kill me too.” And then God sends him back the way he came, to achieve more and greater works than any he had done so far. I take comfort from this story of the weakness of the greatest of all the Old Testament prophets – the prophet who appeared along with Moses at the Transfiguration. Elijah, struck with paralysing discouragement, had to go into a lonely, silent desert and there unburden himself to the Lord of all his frustrations and fears. In that seemingly arid and unpromising place, he drew new strength and was able to answer the question, “Why are you here?” – not with words, but by embarking on a new journey over old terrain: “Go back the way you came”. I am reminded of TS Eliot’s lines from “Four Quartets”: “We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time.” |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed