|

The Desert of Zin in the Negev The journey of Moses took 40 years. It seems to have been a much more tedious journey than that of Abraham, and it is very easy to empathise with Moses’ “murmuring” travelling companions. The Hebrews left Egypt in a blaze of glory. Their years under a cruel oppressor ended with the first Passover, and they crossed the Red Sea on dry land. Their “song of the sea” in Exodus 15 rings with joy and confidence in a delivering God. But, by the time the Hebrews reached the Wilderness of Zin, they had had enough of desert privations. They wanted to return to slavery in Egypt, saying bitterly to Moses and Aaron, "If only we had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the fleshpots and ate our fill of bread; for you have brought us out into this wilderness to kill this whole assembly with hunger." (Ex 16:3)

The miseries of slavery had been forgotten. The past was now viewed selectively and seemed a lot safer and more secure. In contrast, the future they faced with Moses was unknown and comfortless. The Hebrews wanted to reverse their journey. As I have often done. I have often dabbled in the wilderness and then rushed back to the known comfort zones of my own Egypt. How often have I started Lent, for example, with a determination to advance on my journey! How often have I resolutely put behind me the many obstacles to my spiritual progress only to lose heart at the first hurdle! Like Pharaoh’s chariots, my wheels were clogged “so that they turned with difficulty” (Ex 14:25). When the vastness of the wilderness opened up before me, slavery suddenly seemed a lot more attractive. Despite their yearnings for Egypt’s fleshpots, in Exodus 17:1 we read “From the Wilderness of Zin the whole congregation of the Israelites journeyed by stages, as the Lord commanded”. There is no standing still – God asks us to keep moving. As the Hebrews did – but in the next breath we are told that they began to quarrel with Moses again. There was no water to drink, so they asked Moses “Why did you bring us out of Egypt, to kill us and our children and livestock with thirst...Is the Lord among us or not?” Again, the Lord provides, but by the time they reach Rephidim the Hebrews are quarrelling again. So it goes on throughout the Exodus journey – a rollercoaster of ups and downs, of enthusiasm and grumbling, of devotion to God, and worshipping a golden calf. Amid all this, we have the giving of the Ten Commandments, the Ark of the Covenant, the revelation of God’s name and the renewal of God’s covenant with his people. Even within sight of the Promised Land, the people lost heart. The spies they sent to reconnoitre the land came back with reports of a gigantic and powerful people – “to ourselves we seemed like grasshoppers, and so we seemed to them” (Numbers 13:33). The old refrain went up, “Would that we had died in the land of Egypt! Or would that we had died in this wilderness! Why is the Lord bringing us into this land to fall by the sword? Our wives and our little ones will become booty; would it not be better for us to go back to Egypt?” (Num 14: 2-3). Only Caleb and Joshua remonstrated with the people. In anger, God prolonged their sojourn in the wilderness so that none of those alive at that time, with the exception of Caleb and Joshua, would cross into Canaan. The 40 years wandering seems pointless until one realises what was achieved in that time. The people Moses led out of Egypt had been enslaved for four centuries. The Hebrew tribes of Israel entered Egypt voluntarily, probably about 1600 B.C., at the invitation of Jacob’s son Joseph, then a high official in Pharaoh’s administration. They initially prospered, and their numbers multiplied over three centuries. However, “Now a new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph” (Ex 1:8). Under his rule, Hebrews were disenfranchised and forced into slave labour in Egypt’s massive building programme, and in the noxious conditions of the turquoise mines. Their spirit was utterly broken after centuries of bondage. The mixed multitude which set out from Egypt was in no condition to take possession of the land promised to it. In the wilderness years, Moses brought God’s law to the people and welded them together in disciplined monotheism. These “stiff-necked” and vacillating people have been a source of immense encouragement to me: however often they stumbled and longed to turn back, they nonetheless kept moving – urged relentlessly forward by God. They must have longed to stay longer at each oasis – especially at the large oasis of Kadesh Barnea between the deserts of Zin, Shur and Paran where they camped for many years. But, in their subsequent wanderings, the Hebrews were transformed. The murmuring mob became a great nation and the covenant made with Abraham was fulfilled. The Biblical desert is a place of passage and purification. In the desert landscapes of our souls we must learn that God is with us at every stage of the journey. He is God of the wilderness as well as God of the land flowing with milk and honey. However, to reach the latter, we must traverse the former. We, too, need to cast off our inertia and our false gods if we are to enter into the Promised Land.

2 Comments

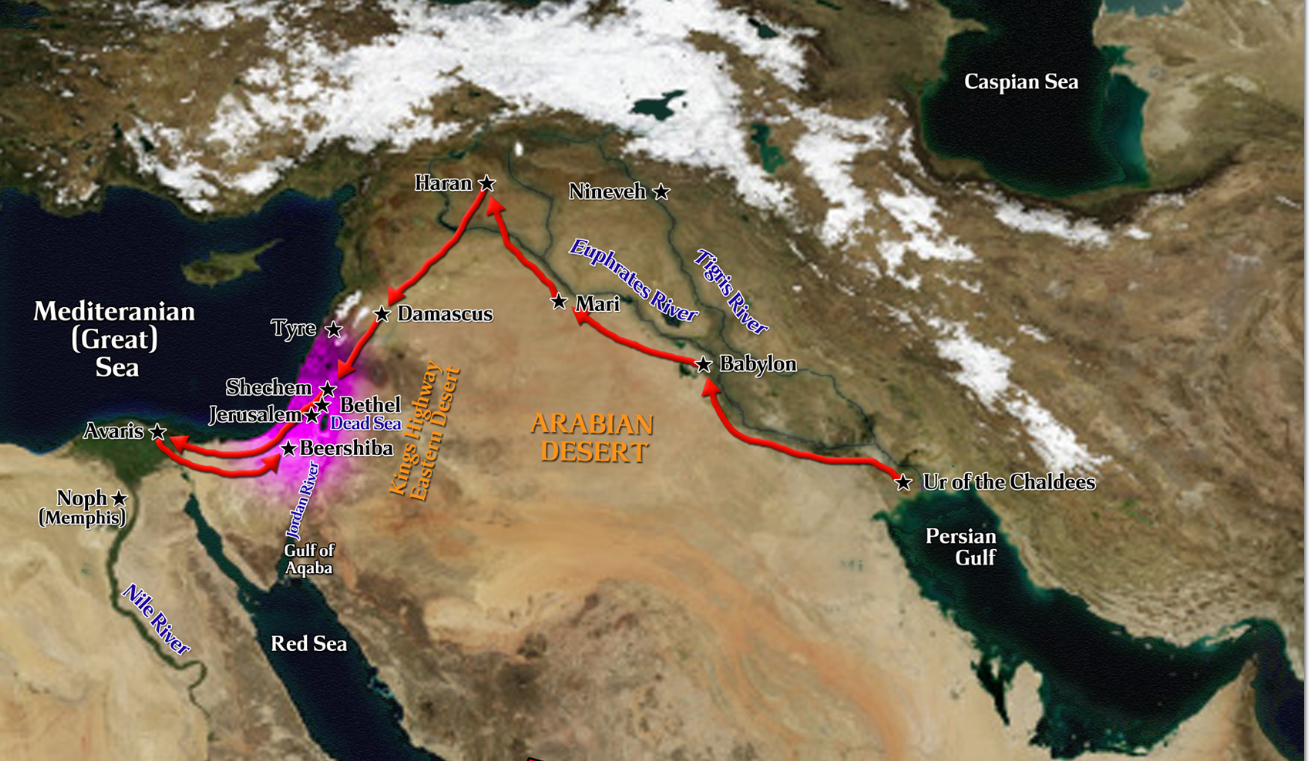

19/2/2018 3 Comments lent week one: "so abram went". I recently came across an article from the New York Times of 13 March 1983, “In the Steps of Abraham”. It began: “The heavy curtains of far-distant time part upon an unlikely stage whose name is Ur. Today, Ur is a desert scrubland with miserable ruins jutting from terrain of sand and mud. It is about 120 miles northwest of the Persian Gulf, in the country we now call Iraq. Unlikely or not, however, very nearly 40 centuries ago, here began a journey that transcended history, and whose arc etched a crescent of hope and faith so indelibly that it determined the motive and course of events for centuries down to this day and far beyond the borders of the nations that were in its path - places we know as Iraq, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Egypt, Jordan.” Ths journey began with a call from God: “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation” (Gen 12:1-2). God’s call is met with many different responses in the Bible. A frequent reaction is reluctance – usually based on a sense of inability to carry out God’s mission. Moses cries out “Who am I, that I should go unto Pharaoh, and that I should bring forth the children of Israel out of Egypt?" (Exodus 3:11). Gideon, called upon to deliver the Israelites from bondage to their Midianite overlords, responds “Pray, Lord, how can I deliver Israel? Behold, my clan is the weakest in Manasseh, and I am the least in my family” (Judges 6:15). Jeremiah pleads youth: “Ah, Lord God! Behold I do not know how to speak, for I am only a youth” (Jer 1:4). With Jonah, actions speak louder than words as, hearing God’s call to go to Nineveh, he promptly takes a ship sailing in to Tarshish, believed to be in southwestern Spain – about as far from Nineveh as anyone could get in the ancient world! Abraham could well have pleaded old age. He was 75 years old and probably looking forward to a tranquil end to his days, when he received the call. He had had more than his share of travelling up to this point. His childhood was in Ur of the Chaldees in what is now south Iraq but, when he was still a boy, his family moved to Haran, in what is now Turkey – a journey of over 600 miles. That journey, while long, was tolerable – following established and well-policed trade routes along the course of the river Euphrates. Now he was being called into utterly uncharted territory. St Paul recognises the magnitude of the challenge: “By faith Abraham, when called to go to a place he would later receive as his inheritance, obeyed and went, even though he did not know where he was going" (Hebrews 11:8). “So Abram went”. As Mary, daughter of Abraham in flesh as well as in faith, will answer “yes” to the divine call two thousand years later, Abraham responded to God’s command. It is an extraordinary acceptance. While he was a monotheist in a polytheistic society (we know from Joshua 24:2 that his own father worshipped idols), Abraham knew far less about God than did Moses, Jeremiah or Jonas. No miracles, no signs accompanied the call; just a promise to this childless man which must have seemed unbelievable. He simply obeyed. We know that he experienced terror on his journey – the opening line of Gen 15 has the Lord saying to him, “Fear not, Abram, I am your shield”. And, again. “As the sun was going down, a deep sleep fell on Abram; and lo, a dread and great darkness fell upon him” (Gen 15:17). He left Haran in southern Mesopotamia (now in modern Turkey) and travelled south-west across Syria and through Damascus. He probably followed the ancient trading route, the “King’s Highway”, from Damascus along the hilly backbone of Jordan and into Canaan. He crossed though Shechem (today the Palestinian town of Nablus) and Bethel; then south to the Judean desert where famine forced him south-west to Egypt and the fertile Nile Delta. After a sojourn in Egypt he retraced his steps through the Judean desert to Canaan, eventually dying at Hebron (where his descendant, David, would be anointed king nearly a thousand years later). The 1,500-mile journey (3,200 miles if one includes the route from Ur to Haran) had no obvious geographic conclusion. However, in the course of it, Abraham found the land which God promised to his descendants; his covenant with God was established; his long-abandoned hopes of a child by Sarah, his wife, were realised; and his name was changed from Abram to Abraham, “the ancestor of a multitude of nations” (Gen 17:5), the spiritual father of the world’s Christians, Jews and Muslims - half of the people alive on earth today. So this is not simply a geographic journey. Abraham could not grow spiritually while he remained comfortably settled in an idolatrous society, never moving out of his comfort zone. Pope St John Paul II, in a homily given on Wednesday, 23 February 2000, asked: "Are we talking about the route taken by one of the many migrations typical of an era when sheep-rearing was a basic form of economic life? Probably. Surely though, it was not only this. In Abraham's life, which marks the beginning of salvation history, we can already perceive another meaning of the call and the promise. The land to which human beings, guided by the voice of God, are moving, does not belong exclusively to the geography of this world. Abraham, the believer who accepts God's invitation, is someone heading towards a promised land that is not of this world." This Lent is an opportunity to leave our own comfort zones, and put behind us the many obstacles to our own spiritual journey. In a noisy world, we can try to be still enough to hear God's voice; and be courageous enough to act on it. Which evokes another quotation from Pope John Paul II: "Have no fear of moving into the unknown. Simply step out fearlessly knowing that I am with you, therefore no harm can befall you; all is very, very well. Do this in complete faith and confidence." 10/2/2018 8 Comments Ash wednesday: into the wilderness“And behold, thou wert within me, and I out of myself, where I made search for thee!” (St Augustine).

This Lent, I am heading for the Judean Desert. Not in body (although I would dearly love to), but in spirit. I have long been fascinated by the unescapable presence of the wilderness in the Old and New Testaments, permeating the Bible as vividly as do any of the Biblical characters. It is always there, its vastness and barrenness a stone’s throw from the habitable world. 'Wilderness' in the Bible refers mainly to two distinct locations: the Sinai Desert, where the Hebrews wandered for 40 years after the exodus from Egypt, and the relatively bare, uncultivated area in the south of the Promised Land known as the Negeb, or Judean Desert. The desert is a place of contradictions – stark, barren, and terrifying. “The great and terrible wilderness” is both a place of trial and of deliverance, of purgation and illumination. Abraham passed through the desert at least twice on his immense migratory journey. This is the place where the wanderings of Moses and his people culminated in the birth of Israel as a nation; here David found refuge from Saul; here the Essenes escaped Hellenistic domination of Jerusalem; here the Zealots made their final, desperate last stand at Masada against the might of Rome; and here John the Baptist prepared for his mission. In the desert Elijah, deeply discouraged, longed for death - but it was here that God came to him in the still, small voice. This is the place where the original scapegoat was sent (Levit 16:10), carrying the sins of the people on his back; and it was to the desert that Jesus – who carried all our sins - was driven by the Spirit. One of Christ’s paradoxical sayings is that we have to lose our life to save it. Equally, we have to go where there are no paths in order to find our direction.The wilderness, or desert, is the ultimate trackless zone. In the Bible it is a place of transformation and revelation. This “howling wilderness waste” (Deut 32:10), swept by deadly winds (Is 21:1; Jer 4:11), is at the same time a holy place, where the glory of God descended upon Moses “like a devouring fire” (Ex 24:17). Passage through the wilderness was an integral part of their mission for Abraham, Moses, John and Jesus. But where is such a place to be found in a modern suburban life? In our frenetic, noisy, peopled world, where are we to find these great stark tracts of silence and isolation, these testing grounds with their lurking dangers of heat and thirst and wild beasts? Where are we to find a place where we strip away everything that is superfluous, everything that distracts us or deadens us, and place ourselves utterly in God’s hands? To find the answer, I plan to retrace the desert journey – sometimes with Abraham, Moses and John – but especially with Jesus, since it is above all in his life that we seek the meaning of our own. The more I read the Biblical accounts, the clearer it became that the journey is metaphorical as well as literal. The wilderness exists on maps, but it also exists within us. For many of us, our “selves” are like haunted houses – tenanted with the ghosts of past loves and losses, triumphs and disappointments, achievements and failures. Sorrows and rage as old as infancy can lurk within us and the accumulation of a lifetime’s shortcomings can make our “selves” uncomfortable and unwelcoming places in which to be, so that we try to spend as much time as possible outside ourselves. We fill our days with noise and activity; sometimes we deaden our pain with alcohol, food, work, sex or drugs. An Episcopal monk and spiritual writer, Martin L Smith, describes our habitual condition as one of being under an anaesthetic: “Most of us have a primary defence mechanism against being overwhelmed by the pain of the world and our own pain. It is as if we administer to ourselves an anaesthetic to numb its impact. The price we pay is that it also numbs our capacity for joy, but until we surrender to the Spirit of God we reckon the price to be worth it.” (Martin M Smith, A Season for the Spirit, London 1991, p.21). Extreme youth or extreme age does not excuse us from making the journey into the wilderness. John the Baptist appears to have entered the desert at a very young age, in preparation for his mission as the Forerunner. Abraham – then known as Abram - was 75 years old when he received that irresistible call “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you” (Gen 12:1). It is almost never too late to make this journey, although the longer we leave it the harder it becomes. Our distractions, addictions or avoidances grow like tumours around vital organs. If we leave the tumours untreated, we die. The longer we wait to remove them, the more potentially deadly the operation. If we don’t confront the wilderness inside, we can never overcome our own isolation. If we don’t sufficiently accept and love ourselves, we can never really enter into communion with others and with God. Was this what St Augustine was getting at when he cried “And behold, thou wert within me, and I out of myself, where I made search for thee!” Next week: Travelling with Abraham |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed