|

14/12/2017 0 Comments O, Come!Detail from the "Madonna Litta”, a late 15th-century painting, traditionally attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, in the Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg Our first and only child was born at ten minutes to midnight on December 23rd.

I have always loved the season of Advent; that year, when I was expecting a Christmas baby, I found the Advent liturgies almost unbearably moving. In my yearning expectancy, the great ‘O’ antiphons, with their longing and mounting impatience, resonated with me as never before. It seemed to me that all the mystery of creation was contained within me. I waited for the birth with heart stopping excitement. And, through those final days of pregnancy, the beautiful, sombre rhythms of the O Antiphons seemed almost the rhythms of life itself. They are sung as though with breath held, suffused with reverence and wonder. “O come, o come” - the verb veni is repeated again and again “recalling an urgent eschatological prayer so ancient that it was offered in the native Aramaic by the earliest Christian church… It embodies the deep yearning of the exiles in the Babylonian captivity for freedom, of the post-exilic Jews for the restoration of former glories perhaps personified in the Messiah, and of the primitive church for a speedy return of its ascended Master. It is an intense prayer epitomizing all prayers whatever their content.” [1] “O come Lord Jesus” – the fervent request is as old as St Paul [2] and forms the penultimate verse of the book of Revelation and thus of the New Testament. All of these associations were with me in those final days. I felt as old as Eve, participating in the act of Creation. I woke before dawn on the eve of Christmas Eve, to the certain knowledge that our baby was on the way. Eighteen hours later, it seemed as though this baby would never be born. “Labour” is accurately named. For the previous many hours contractions had been sweeping in like tidal waves, each one picking me up like a tiny piece of flotsam and bearing me down into a new tunnel of pain and exhaustion. I no longer believed that this cruel effort was going to produce anything at all. In the brief respites between contractions I withdrew from time and the world. Inexorably drawn back by the next wave, I was surprised to find myself still there. And so it went on, hour after hour – wholly relentless, unavoidable. And then, stunning pain, pain to take the breath away, and I began to know fear. The urge to deliver the baby was inexorable – but it seemed like an urge to self-destruct. I could no more avoid it than I will be able to avoid death. Then the moment came when, at last, with a final crescendo of effort, our baby was there. I held her warm living body against me, looked into her astonishingly calm eyes and instantly, irrevocably, fell in love. She glided around my heartstrings like running water, to crystallise there - so that my heart was no longer mine but was from then on a part of her. This, then, or something like it, Mary went through. In blood and sweat and pain she went through this most elemental of experiences, lying on the mud floor of an outhouse. In the words of the opening prayer of the Dawn Mass on Christmas Day, “Almighty God… your Eternal Word leaped down from heaven in the silent watches of the night, and now your Church is filled with wonder at the nearness of her God.” The maker of the universe passed through a female womb and lay helpless and beloved on his mother’s breast as my baby did on mine. Mary must have gazed on the infant Jesus with the same wonder that mothers have felt since Eve bore the first child in creation. Her first baby, for every woman, is the first baby in the world. Nobody will have gone through a pregnancy and delivery exactly like hers. Ask any mother about her child’s birth, and the story will be absolutely unique to that mother and that baby. Nobody will feel the same sense of wonder at this particular miracle of creation. Eve’s shout of triumph after the birth of Cain still echoes down the millennia: “I have gotten a child with the help of the Lord!” On that night in Bethlehem, God became our travelling companion on life’s journey. He took on our human condition, and became subject to illness, to aging and to death. As the weeks passed, and as I held our infant daughter in my arms, feeling the warmth of her downy little head and her tiny fingers with the nails I didn’t dare to cut moving like small, lovely spiders over my skin, I thought the universe itself could not contain my wondering love. And when she smiled for the first time, the radiance lit my world from end to end. For the first time, I began to have some infinitesimal sense of God’s love for his creation. [1] Allen Cabaniss, “A Jewish Provenience of the Advent Antiphons?” The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Ser., Vol. 66, No. 1. (Jul., 1975), pp. 39-56. [2] 1Cor16:22

0 Comments

12/9/2017 0 Comments The Book of jobThe book of Job is generally held to be the oldest book in the Bible. It was circulated orally in the second millennium B.C. and written down in Hebrew at roughly the time of David and Solomon. For a depiction of God’s exuberant creative force, it took the story of long-suffering Job to make the hair stand on the back of my neck.

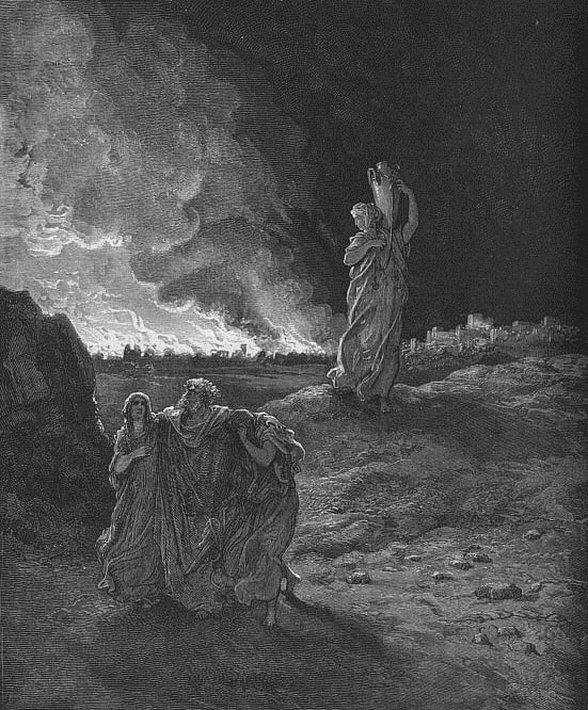

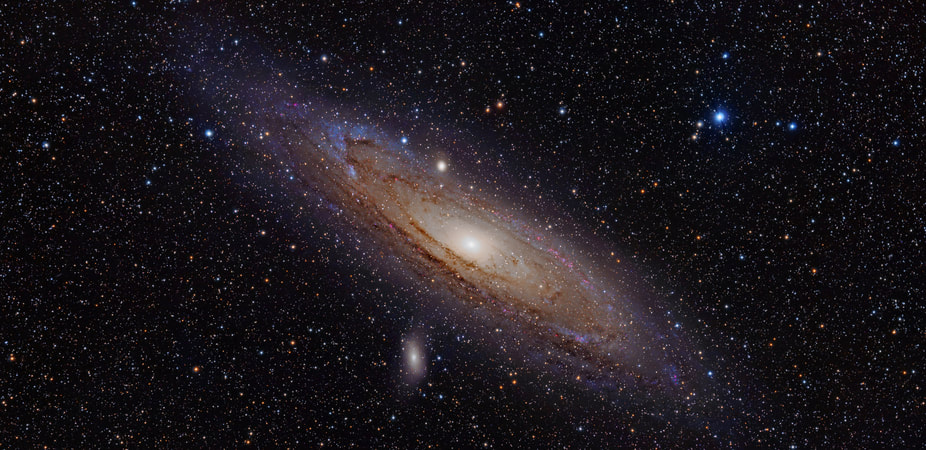

Throughout his many trials, Job steadfastly refuses to curse God. However, his sense of injury and outrage build up to a furious climax in which he demands to see God and question him face to face about the justice of his actions. He concludes with a ringing demand for justice: “Oh, that I had one to hear me! (Here is my signature! Let the Almighty answer me!)” (31:35). “Signature” literally means “taw”, the last letter in the Hebrew alphabet. This is Job saying: “This is my last word. Answer me!” “Signature” literally means “taw”, the last letter in the Hebrew alphabet. This is Job saying: “This is my last word. Answer me!” And the Almighty does respond to this audacious demand, in a sublime poem that lasts five chapters (38-41). In sweeping verse, he presents a series of questions to Job, asking where he was when God created the earth, the tumultuous sea, dawn grasping the earth by its skirts, the gates of night, the elements and the constellations, all animals and living things. The language is magnificent, conveying a sense of beauty, majesty, mystery and power that has hardly been equalled in the thousands of years since it was written. The first time I really experienced Scripture as inspired writing was when I first encountered the Book of Job. “Where were you”, God asks Job, “when I laid the foundation of the earth? …When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?” “Who shut in the sea with doors, when it burst forth from the womb; when I made clouds its garment, and thick darkness its swaddling band?” “Have the gates of death been revealed to you?” “Have you entered the storehouses of the snow?” “Can you bind the chains of the Pleiades, or loose the cords of Orion?” And so it goes on, this extraordinary journey through the created universe, question after question, with the refrain: “I will question you and you will declare to me. Will you put me in the wrong? Will you condemn me that you may be justified?” God gives no verbal answer to Job’s question as to why the innocent are permitted to suffer, nor does he see why he should. He does not “owe” Job an explanation: “Who has given to me, that I should repay him? Whatever is under the whole heaven is mine” (Job 41:11). The notes to Job, Chapter 42, in the New Oxford Annotated Bible (1971) offer this commentary: God has not justified Job, but he has come to him personally; the upholder of the universe cares for a lonely man so deeply that he offers him the fullness of his communion. Job is not vindicated but he has obtained far more than a recognition of his innocence: he has been accepted by the ever-present master-worker, and intimacy with the Creator makes vindication superfluous. The philosophical problem is not solved, but it is transfigured by the theological reality of the divine-human rapport. All that is left is for Job to accept the inscrutable grace of the God “whose thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways…For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways” (Isa 55:8,9). The conclusion of the story is told briefly and in prose, as Job’s fortunes are restored and he dies “an old man, and full of days”. It was Job’s plain speaking and determination which wrested that mighty response from God. Job did not hesitate to engage honestly with God. He spoke what was on his mind and God honoured him for it. It seems a relatively simple thing to do, to tell God what you are thinking, but it isn’t. Which of us has not been haunted at some time or other by the fear that everything we believe is a delusion – the stuff of a fable told to a child to allay his fear of the dark? How often have we acknowledged that fear to ourselves, let alone to God? Or the many other terrors, resentments, hatred and guilt that drain our lives of joy and hope? If we are to mend something that is broken, we must first be able to look at the break. Job described his own wretchedness pitilessly, in words that resonate with us four thousand years later. It is all here, the absence and the silence of God, the prosperity of the wicked, the broken spirit, the raging against fate. But underlying it all is the refusal to give up, the refusal to be silent – the same capacity of endurance that marked even the most flawed of the biblical protagonists. Even before God succumbs to this relentless battering at his door, Job can express hope. In this, the Bible’s oldest book, the gloom and desolation of Sheol is displaced by the first expression of belief in life after death: For I know that my Redeemer lives, and that at the last he will stand upon the earth; and after my skin has been thus destroyed, then in my flesh I shall see God. (Job 19:25, 26) 17/7/2017 0 Comments Lot's Wife I was very young when I first encountered the story of Lot’s wife, accompanied by a woodcut slightly similar to the Gustave Doré engraving above. Across the passage of many years, I can see that black and white picture with astonishing clarity. In the foreground Lot and his daughters are hurrying upward, away from the sulphurous blast which is laying waste the landscape behind them. The entire background is occupied by blinding sheets of light, suggesting the cataclysm taking place below. Most chilling of all to my child’s eye, however, was the still grey figure of Lot’s wife, in the centre of the picture. Even as her upper body is in the act of turning, her feet are already frozen forever. It was a shocking evocation of instantaneous, brutal retribution. As I became more familiar with the story in later years, my puzzlement intensified. Lot’s wife’s offence seems to pale in comparison with the activities of her deeply unpleasant husband. Yet he is spared, to commit further disgraceful acts. What was so terrible about his wife disobeying a command not to look back? When I first saw the picture, I couldn’t understand why Lot’s wife would have wanted to turn back in the first place. But then, at that time of my life, I was untouched by the force field of the past. Forty years or so later, my perspective has changed. I now understand – through my own experience and that of others - what it can be to be imprisoned by the past. The shackles can take many forms - nostalgia, remorse, resentment, an overwhelming attachment to things and places. The past is so safe – a finite thing, defined in space and time, containing no surprises. It is like an old shoe – it may not be ideal for a long journey, but it slips on easily and requires no breaking in. How often do we seek security rather than fulfilment? How often are we frozen between where we have been and where we should go? As Lot and his family flee the cataclysmic upheaval in Sodom, “Lot’s wife behind him looked back, and she became a pillar of salt”. Why the terrible fate? She looked back. This is reinforced by the context in which Christ refers to her. As described by Luke, the Pharisees have raised the question about the coming of the kingdom of God and he answers them briefly. Then he turns to his own followers and elaborates: And he said to his disciples…on the day when Lot went out from Sodom fire and sulphur rained from heaven and destroyed them all – so will it be on the day when the Son of Man is revealed. On that day, let him who is on the housetop, with his goods in the house, not come down to take them away; and likewise let him who is in the field not turn back. Remember Lot’s wife. Whoever seeks to gain his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life will preserve it. [1] The downfall of Lot’s wife, then, was in her refusal to believe that this – for her – was the day of salvation. When Christ speaks of the desire to save one’s life, he is speaking of a desire to preserve our own definition of life. Very often, we see life in terms of who we are, what we do and what we possess. Our energies go into preserving the illusion of control over all of this. To “lose” this life is to relinquish control, to allow ourselves, in the words of the 12th century Hildegard of Bingen, to be “blown like a feather on the breath of God”. Lot’s wife was unable to trust herself to trust God. In seeking to hold on to her life as she knows it, she lost everything. Lot’s wife couldn’t move forward because of the pull of the past. She couldn’t even move back. And many of us have been Lot’s wife too – frozen into immobility. I have been on the housetop when the Lord gave a warning I could not fail to hear, and yet I turned back into the house despite the warning to leave everything. What is it that pulls me back into the house? What is it that lets me hear the call of God and still linger? How many times have I put my hand to the plough and still turned back? The door through which the Lord calls me is always open, but on my last day on earth it will close forever. Which side of the door will I be on then? [1] Luke 17:22, 29-33 Helen is part of the team at New Pilgrim Path. 3/6/2017 0 Comments "Simon peter, do you love me?"At his first meeting with Christ after the Resurrection, Peter is asked three times by Jesus, "do you love me?" And vacillating Peter moves on from the shame of his threefold denial of Christ to become the rock on which Christ’s church was founded.

It may be hard to forgive, but it can be harder to ask for and accept forgiveness. The ability to believe we are forgiven is crucial to our spiritual growth. This was the defining difference between Peter and Judas. Judas could not contemplate the possibility of forgiveness. He, who had heard Christ say that one must forgive seventy times seven, could not bring himself to ask Christ to forgive him. Instead, he died in despair. It’s easy to forget the other side of the coin – if we must be prepared to forgive seventy times seven (i.e. limitlessly), then we must also be ready to ask for forgiveness – and believe we are forgiven - seventy times seven. Self loathing leads inevitably to despair. Thomas Merton describes the process: Despair is the ultimate development of a pride so great and so stiff-necked that it selects the absolute misery of damnation rather than accept happiness from the hands of God and thereby acknowledge that He is above us and that we are not capable of fulfilling our destiny by ourselves. [1] [1] Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation, (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2003) 180 27/5/2017 1 Comment The Ascension Lord, do I really believe that you lived on earth, died and arose to everlasting life? If I did, surely I would be more able to recognise you in the hearts of others, in Scripture, in the Sacraments? But, surrounded as I am with your presence, I am often as unable to recognise it as were Cleopas and his companion on the road to Emmaus. Unable, because like them, like the Apostles, too, I am so often not expecting to find it. To Cleopas and his friend, the revelation came after long listening. I know I do not listen enough. I besiege you with words, but I do not wait for a response. Perhaps, in my heart of hearts, I do not expect a response. Lord, strengthen my faith - that faith which will give me eyes that see, and ears that hear; that faith which will reveal your luminous presence at the very heart of myself. Then, I may begin the long ascent. And I remind myself that, for you, without the descent among the dead there could have been no ascension. Without Good Friday, there could have been no Easter Sunday. Lord, grant that one day I may go where you are, and behold the glory the Father gave you before the foundation of the world. 13/5/2017 1 Comment Jacob Wrestling At this time of year, the Church readings are from the Acts of the Apostles. We have had the dramatic conversion of Saul, and his renaming as Paul. It reminds me of one of several other renamings in the Bible, that of Jacob to Israel. One of the most haunting episodes in Genesis is the wordless night long wrestle between duplicitous Jacob and the mysterious figure at the ford of the Jabbok, on the north-eastern frontier of the Promised Land. The eerie battlefield on the banks of the Jabbok is universal. Somewhere along our journey, most of us will find ourselves there. As with Jacob, there comes a time when, in order to go forward, we must first stop. We have to stand back from everybody and everything in our lives and - utterly alone with ourselves - confront all the compromises we have made. In order to find our way, we have to go deep into the trackless dark and grapple with our demons. While the world slept, Jacob fought for his survival, unable even to see the face of his adversary. As dawn crept over the horizon, the first words were spoken. Jacob’s opponent said, “Let me go, for the day is breaking”. “I will not let you go”, Jacob said between clenched teeth, “unless you bless me”. Before he would bless Jacob, the angel forced a confession from him. “What is your name?” he asked. And Jacob was forced into admitting, “I am Jacob”. In ancient narrative, one's personality and one’s very self were inextricably linked with one's name; a name held a person’s destiny. In giving his name, Jacob was confessing to everything that has marked his life to date, “I am the one who supplants; the one who grasps what is not his, the one who deceives”. When Jacob admitted his name, the response was immediate. “Your name shall no more be called Jacob, but Israel (literally “he who strives with God”), for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed”. As with other Biblical figures (Abram/Abraham, Simon/Peter, Saul/Paul), a change of name indicated a new beginning. “Who are you?” “Jacob.” By renaming him, God is saying “No, you are more than you think you are.” When we find ourselves on that dark and lonely battlefield, wrestling with God, we need to bear in mind that the outcome of the wrestling will determine whether we will receive God’s blessing, and whether we will receive the strength to be reconciled with our past and our present We will know that we, too, are no longer Jacob, but Israel. The words of Matheson’s moving hymn will pierce us with their relevance: O Love that wilt not let me go, I rest my weary soul in thee; I give thee back the life I owe, that in thine ocean depths its flow may richer, fuller be. Picture above is Jacob Wrestling with the Angel by Delacroix, in the Church of Saint-Sulpice, Paris. 20/4/2017 1 Comment April 20th, 2017"A GOD WHO DANCES"  “If these Christians want me to believe in their god, they’ll have to sing better songs, they’ll have to look more like people who have been saved, they’ll have to wear on their countenance the joy of the beatitudes. I could only believe in a god who dances.” These sentiments of Nietzsche will strike a chord with many Christians. Thomas Merton draws an extraordinary picture of God playing in the garden of his own creation and adds: "If we could let go of our own obsession with what we think is the meaning of it all, we might be able to hear His call and follow Him in His mysterious cosmic dance. We do not have to go very far to catch echoes of that game, and of that dancing. When we are alone on a starlit night… when we see children in a moment when they are really children; when we know love in our hearts…at such times the awakening, the turning inside out of all values, the ‘newness’, the emptiness and the purity of vision that make themselves evident, provide a glimpse of the cosmic dance." According to Merton, the more we try to analyse life, the more we involve ourselves in sadness. “But it does not matter much because no despair of ours can alter the reality of things, or stain the joy of the cosmic dance which is always there. Indeed, we are in the midst of it, and it is in the midst of us, for it beats in our very blood, whether we want it to or not”. [1] It may beat in our blood, but we still deny it. It is too easy to live in the created world as though in a transparent capsule - seeing, but feeling no sense of identity with, creation. There have been so many times when I have felt no real sense of being constantly in the Creator’s presence, let alone belonging there; no sense of interconnectedness with the rest of creation. I glided along the surface of the spinning earth, never listening to its heartbeat. I looked into the depths of the universe, and never heard the singing of the stars. Unlike the Psalmist, I never saw the mountains skipping like rams (Ps 114) or watched the wilderness bloom. I lived beside the sea, but without sharing the Psalmist’s wonder at “its vast expanses teeming with countless creatures, creatures both great and small; there ships pass to and fro, and Leviathan whom you made to sport with.” (Ps 104:25-26) [1] Merton, Thomas, OCSO, New Seeds of Contemplation (New York: Penguin Books (New Directions Paperback) 1972) pp 296-7.  As Good Friday approaches, I listen again to that cry from the Cross, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”As Good Friday approaches, I listen again to that cry from the Cross, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” And, once again, I wonder why it is so rarely read in context. Throughout the Gospels, Jesus always addresses his Father with the familiar form of address, "Abba". Here, on the Cross, he shifts to the formal "Eli" or "Eloi". This has been interpreted as an indication of the depth of Jesus' sense of abandonment. However, there could be a much simpler reason for his choice of address. "Eli, Eli, lama sabachtani" are the opening words of Psalm 22, and any devout Jew at the foot of the Cross would have known this Psalm, line for line. The chief priests, scribes and elders gathered below him must be stopped dead in their tracks - they who, a few minutes earlier had wagged their heads at him, saying derisively: “He trusts in God; let God deliver him now, if he desires him” (Mt 27:43). “All who see me mock at me” says the Psalm, “they make mouths at me, they wag their heads; ‘He committed his cause to the Lord; let him deliver him, let him rescue him, for he delights in him!’” Does a stillness fall upon the crowd, broken only by the rattling of the dice? “…they have pierced my hand and feet… they divide my garments among them; and for my raiment they cast lots.” Do their minds race ahead to the prayer for deliverance that comes next in the Psalm: “But thou, O Lord, be not far off!” Is it at this point they begin - derisively? a little uncertainly? - to mutter, “Wait, let us see whether Elijah will come to save him” (Mt 27:49). The ringing conclusion of the Psalm is a long way removed from the despair of the opening: “men shall tell of the Lord to the coming generation, and proclaim his deliverance to a people yet unborn”. The words may be at once a warning to the hostile, and a comfort to the faithful. He has nearly done. Far from being a cry of despair, are Jesus' words not a shout of triumph? |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed