|

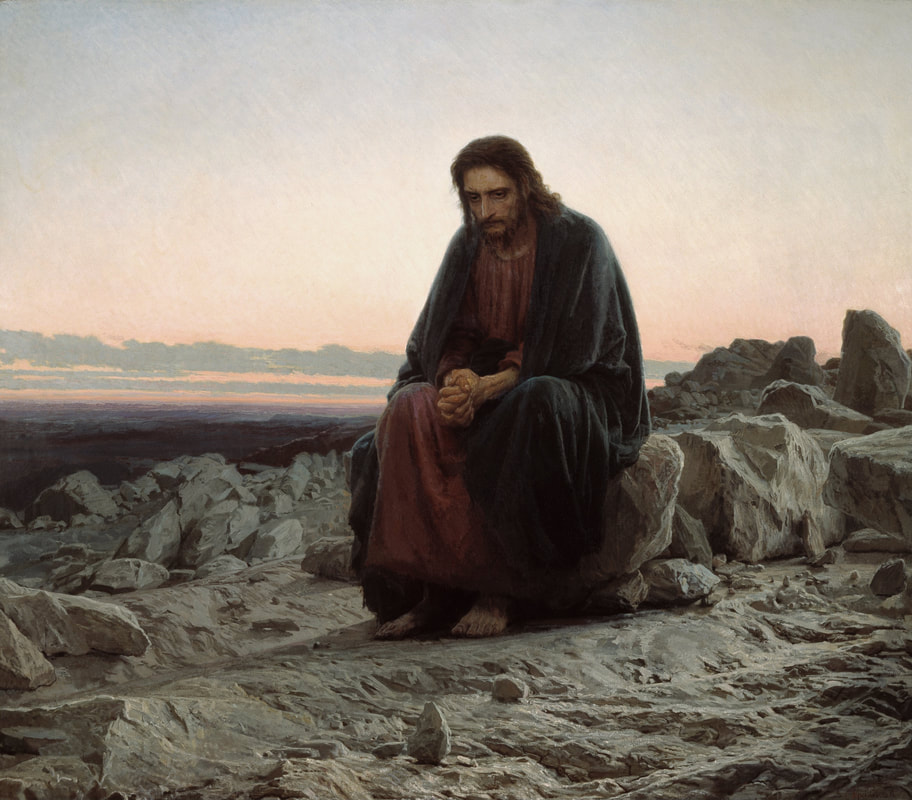

The above image, Ivan Kramskoi's Christ in the Desert (1872,Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), powerfully captures - for me anyway - the vulnerability of Jesus in his desert sojourn.

Like the Hebrews leaving Egypt, we have to ease off the shackles of slavery to false gods. The false gods are different for each of us – a desire for money, status or power, an addiction, an old resentment or hatred, an extramarital love affair, an obsession with work, a refusal to advance on our journey for fear that we may not be able to complete it – but all have this in common: the false gods displace the real God for us. They drain our energies and our hope. Life with them has no savour; life without them is unimaginable – a wilderness too huge and bare to contemplate. We have become so accustomed to our enslavement that our chains have grown comfortable. We sit by our “fleshpots”; we “eat our bread to the full”. We shrink before the colossal aridity of the desert. Better the devil we know than the one we do not. Even Jesus had to be “driven” into the wilderness, where he fasted for 40 days, as Elijah did before him. Just as he shared our human nature, our birth and growing pains, our loves and terrors, Jesus allowed himself to be tested as we all must be tested. If what is tested in us is our weakest point, then the temptation of Jesus seems to centre on his feelings about his mission. Twice Satan says “If you are the Son of God…” Does this suggest that Jesus himself is not certain about who he is? It is easy to empathise with him if this is so. It is easy to feel disbelief in our own worth and destiny. It is so easy to deny the colossal reality that we are living temples, in which the Word of God is eternally spoken. The wild beasts of Christ’s wilderness haunt our internal landscapes too - beasts of terror, rage and despair. So, we turn to Jesus and see how he coped. “If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become bread,” the devil said. Christ’s reply, “Man shall not live by bread alone” is a direct quotation from Moses in the wilderness, addressing his vacillating followers. (Deut 8:3). It speaks directly to us today – we can starve in the desert of our souls without the word of God to feed us. Satan, bringing Jesus to the pinnacle, invites Jesus to test whether he is, indeed, the One the psalmist wrote about, “For he will command his angels concerning you, to guard you in all your ways. On their hands they will bear you up, so that you will not dash your foot against a stone” (Ps 91:11-12). Again, Jesus quotes Moses, “Do not put the Lord your God to the test.” (Deut 6:16). The striking parallels which Christ draws between his 40 days in the desert and the Israelites’ 40 years in the wilderness are full of significance. Jesus emphasises our dependence on God, and our inability to accelerate our passage to the Promised Land. Satan was offering a quick fix to any doubts Jesus may have had, and Jesus turned it down. There are no short cuts on our journey. The Promised Land was not a 40-year journey from Egypt, but 40 years was what it took to prepare the Israelites to take possession of the Promised Land. In recalling the experience of the 40 years' wandering, there is another subtext. The Israelites faced a massive recurring temptation which we, too, encounter: the desire to say “enough – we’ve tried this and it isn’t working. Let’s turn back”. But they found that God is Lord of the wilderness as well as Lord of the oasis. The only way we can know that is to experience it. It may be a long and a hard journey to the Promised Land, but the only way to get to it is across the desert. The alternative is to stagnate in our own particular Egypts. If we do that, we will never experience transformation in, and transformation of, the desert. By saying, “I can’t go any further”, we will be the earthen vessels striving with the potter, “Woe to you who strive with your Maker, earthen vessels with the potter! Does the clay say to the one who fashions it, ‘What are you making?’ or ‘Your work has no handles?’" (Isa 45:9) The Promised Land is waiting for us to take possession of it – not tomorrow, not in some faraway time when we will have dispensed with all the things that now distract us or anaesthetise us, but now. As God said to Moses on the hills of Moab, within sight of the Promised Land, “This commandment that I am commanding you today is not too hard for you, neither is it too far away. It is not in heaven, that you should say, ‘Who will go up for us to heaven for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?’ Neither is it beyond the sea, that you should say, ‘Who will cross to the other side of the sea for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?’ No, the word is very near to you; it is in your mouth and in your heart for you to observe”. (Deut 30:14) If we have the courage to place ourselves in the hands of our Maker, we will feel the heavens open and rain grace down upon us, transforming our desert: The wilderness and the dry land shall be glad, the desert shall rejoice and blossom; like the crocus it shall blossom abundantly, and rejoice with joy and singing. (Isa 35:1) We will hear the words of Moses to the Israelites as they emerge from the wilderness and understand that: "The eternal God is your refuge, and underneath are the everlasting arms." (Deut 33:27). We will know that angels have ministered to us without our realising it. And, because Christ went through the same experience, we will be able to take comfort in the knowledge that he is both the Way and the Wayfarer.  In the Bible, God communicates with his people in many different ways – most of them very loud! He speaks through a whirlwind in Job, an earthquake in Exodus and Hebrews, a voice like thunder in Samuel, Job, Psalm 104, and John. His address to Ezekiel is preceded by a storm and a “sound of tumult”; in Revelation, thunder and lightening rumble and flash around his throne. In only one place in the Bible does he speak in a “still, small voice”, and that is during his interchange with Elijah in the Judean Desert. When Abraham and Moses entered the desert, it was as part of a journey forward. Elijah, in contrast, was retreating - from the terrifying wrath of his arch enemy, Queen Jezebel. He fled first from the Northern Kingdom to Beersheba, a journey of about 260 miles, and then from Beersheba into the Judean desert. The desert was less a geographical location than a spiritual point in Elijah’s earthly pilgrimage, as it had been for the Israelites 600 years earlier. The true desert – where purification takes place - is not outside us, but within. Like a physical desert, our internal wilderness can be a place where we feel terrifyingly alone and in which we want to spend as little time as possible. Yet, it is only in this - at best inhospitable and at worst dangerous - place that we can encounter God. Even Jesus, the “new Elijah”, had to enter the desert – “driven” by the Spirit. This is a place in which we can be tempted by indifference, by lethargy, by fear, by despair, by self-doubt – “I can’t do this thing”. The Elijah of 1 Kings, Chapter 18 is a formidable man, standing alone on Mount Carmel against 450 prophets of Baal and a hostile king. He puts the prophets of Baal to the test, challenging them to bring fire to the earth through their prayers to Baal, and then himself successfully calling down fire and then water from heaven. He does not doubt for a moment that God will respond to his call. He triumphs over the false prophets and cows the sinister king, who goes back to his wife, Jezebel, and tells her all that Elijah had done. This rekindles her anger and she vows to have Elijah’s life. Having provided such spectacular proof that Yahweh is indeed God, Elijah confidently expected that the apostate Israelites would return to the true path. It didn’t happen. The only communication after the triumph on Mount Carmel was Jezebel’s death threat. It is astonishing to see how quickly terror takes over this towering Old Testament figure. Despite the many proofs he has had of God’s power and support, he runs for his life from an angry woman. By the time he enters the desert, he has given up all hope, and all faith in his mission. At the end of a day’s journey, he cries out in fear and exhaustion, “I have had enough, Lord. Take my life; I am no better than my ancestors.” Elijah is saying “I am not the person you think I am, Lord. I can’t do these things you ask of me. Don’t ask me to do any more.” Fear has given way to something more insidious, the state of acedia - described by Aquinas as “the sorrow of the world that wreaks spiritual death”, and by St John Cassian as the “noonday demon”. It is so easy to identify with Elijah here. Times of immense faith can evaporate in seconds, giving way to torpor and listlessness. Instead of living, we exist. And yet, there is much hope in this grim episode in the story of Elijah. In the loneliness of the desert, an angel comes to bring three nights of sound sleep and good sustenance. Then, refreshed, Elijah journeys 40 days and 40 nights to Mount Horeb, where in the silence of the desert, after the wind and the fire and the earthquake have passed, he is able to hear God’s “still, small voice” which gently asks him “Why are you here, Elijah?” Twice he asks, and twice Elijah is allowed to get all his grievances off his chest ““I have been very zealous for the Lord God Almighty. The Israelites have rejected your covenant, torn down your altars, and put your prophets to death with the sword. I am the only one left, and now they are trying to kill me too.” And then God sends him back the way he came, to achieve more and greater works than any he had done so far. I take comfort from this story of the weakness of the greatest of all the Old Testament prophets – the prophet who appeared along with Moses at the Transfiguration. Elijah, struck with paralysing discouragement, had to go into a lonely, silent desert and there unburden himself to the Lord of all his frustrations and fears. In that seemingly arid and unpromising place, he drew new strength and was able to answer the question, “Why are you here?” – not with words, but by embarking on a new journey over old terrain: “Go back the way you came”. I am reminded of TS Eliot’s lines from “Four Quartets”: “We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time.” The journey of Moses took 40 years. It seems to have been a much more tedious journey than that of Abraham, and it is very easy to empathise with Moses’ “murmuring” travelling companions. The Hebrews left Egypt in a blaze of glory. Their years under a cruel oppressor ended with the first Passover, and they crossed the Red Sea on dry land. Their “song of the sea” in Exodus 15 rings with joy and confidence in a delivering God. But, by the time the Hebrews reached the Wilderness of Zin, they had had enough of desert privations. They wanted to return to slavery in Egypt, saying bitterly to Moses and Aaron, "If only we had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the fleshpots and ate our fill of bread; for you have brought us out into this wilderness to kill this whole assembly with hunger." (Ex 16:3)

The miseries of slavery had been forgotten. The past was now viewed selectively and seemed a lot safer and more secure. In contrast, the future they faced with Moses was unknown and comfortless. The Hebrews wanted to reverse their journey. As I have often done. I have often dabbled in the wilderness and then rushed back to the known comfort zones of my own Egypt. How often have I started Lent, for example, with a determination to advance on my journey! How often have I resolutely put behind me the many obstacles to my spiritual progress only to lose heart at the first hurdle! Like Pharaoh’s chariots, my wheels were clogged “so that they turned with difficulty” (Ex 14:25). When the vastness of the wilderness opened up before me, slavery suddenly seemed a lot more attractive. Despite their yearnings for Egypt’s fleshpots, in Exodus 17:1 we read “From the Wilderness of Zin the whole congregation of the Israelites journeyed by stages, as the Lord commanded”. There is no standing still – God asks us to keep moving. As the Hebrews did – but in the next breath we are told that they began to quarrel with Moses again. There was no water to drink, so they asked Moses “Why did you bring us out of Egypt, to kill us and our children and livestock with thirst...Is the Lord among us or not?” Again, the Lord provides, but by the time they reach Rephidim the Hebrews are quarrelling again. So it goes on throughout the Exodus journey – a rollercoaster of ups and downs, of enthusiasm and grumbling, of devotion to God, and worshipping a golden calf. Amid all this, we have the giving of the Ten Commandments, the Ark of the Covenant, the revelation of God’s name and the renewal of God’s covenant with his people. Even within sight of the Promised Land, the people lost heart. The spies they sent to reconnoitre the land came back with reports of a gigantic and powerful people – “to ourselves we seemed like grasshoppers, and so we seemed to them” (Numbers 13:33). The old refrain went up, “Would that we had died in the land of Egypt! Or would that we had died in this wilderness! Why is the Lord bringing us into this land to fall by the sword? Our wives and our little ones will become booty; would it not be better for us to go back to Egypt?” (Num 14: 2-3). Only Caleb and Joshua remonstrated with the people. In anger, God prolonged their sojourn in the wilderness so that none of those alive at that time, with the exception of Caleb and Joshua, would cross into Canaan. The 40 years wandering seems pointless until one realises what was achieved in that time. The people Moses led out of Egypt had been enslaved for four centuries. The Hebrew tribes of Israel entered Egypt voluntarily, probably about 1600 B.C., at the invitation of Jacob’s son Joseph, then a high official in Pharaoh’s administration. They initially prospered, and their numbers multiplied over three centuries. However, “Now a new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph” (Ex 1:8). Under his rule, Hebrews were disenfranchised and forced into slave labour in Egypt’s massive building programme, and in the noxious conditions of the turquoise mines. Their spirit was utterly broken after centuries of bondage. The mixed multitude which set out from Egypt was in no condition to take possession of the land promised to it. In the wilderness years, Moses brought God’s law to the people and welded them together in disciplined monotheism. These “stiff-necked” and vacillating people have been a source of immense encouragement to me: however often they stumbled and longed to turn back, they nonetheless kept moving – urged relentlessly forward by God. They must have longed to stay longer at each oasis – especially at the large oasis of Kadesh Barnea between the deserts of Zin, Shur and Paran where they camped for many years. But, in their subsequent wanderings, the Hebrews were transformed. The murmuring mob became a great nation and the covenant made with Abraham was fulfilled. The Biblical desert is a place of passage and purification. In the desert landscapes of our souls we must learn that God is with us at every stage of the journey. He is God of the wilderness as well as God of the land flowing with milk and honey. However, to reach the latter, we must traverse the former. We, too, need to cast off our inertia and our false gods if we are to enter into the Promised Land. 4/3/2022 Lent Week One: 'So Abram went...'I recently came across an article from the New York Times of 13 March 1983, “In the Steps of Abraham”. It began:

“The heavy curtains of far-distant time part upon an unlikely stage whose name is Ur. Today, Ur is a desert scrubland with miserable ruins jutting from terrain of sand and mud. It is about 120 miles northwest of the Persian Gulf, in the country we now call Iraq. Unlikely or not, however, very nearly 40 centuries ago, here began a journey that transcended history, and whose arc etched a crescent of hope and faith so indelibly that it determined the motive and course of events for centuries down to this day and far beyond the borders of the nations that were in its path - places we know as Iraq, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Egypt, Jordan.” Ths journey began with a call from God: “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation” (Gen 12:1-2). God’s call is met with many different responses in the Bible. A frequent reaction is reluctance – usually based on a sense of inability to carry out God’s mission. Moses cries out “Who am I, that I should go unto Pharaoh, and that I should bring forth the children of Israel out of Egypt?" (Exodus 3:11). Gideon, called upon to deliver the Israelites from bondage to their Midianite overlords, responds “Pray, Lord, how can I deliver Israel? Behold, my clan is the weakest in Manasseh, and I am the least in my family” (Judges 6:15). Jeremiah pleads youth: “Ah, Lord God! Behold I do not know how to speak, for I am only a youth” (Jer 1:4). With Jonah, actions speak louder than words as, hearing God’s call to go to Nineveh, he promptly takes a ship sailing in to Tarshish, believed to be in southwestern Spain – about as far from Nineveh as anyone could get in the ancient world! Abraham could well have pleaded old age. He was 75 years old and probably looking forward to a tranquil end to his days, when he received the call. He had had more than his share of travelling up to this point. His childhood was in Ur of the Chaldees in what is now south Iraq but, when he was still a boy, his family moved to Haran, in what is now Turkey – a journey of over 600 miles. That journey, while long, was tolerable – following established and well-policed trade routes along the course of the river Euphrates. Now he was being called into utterly uncharted territory. St Paul recognises the magnitude of the challenge: “By faith Abraham, when called to go to a place he would later receive as his inheritance, obeyed and went, even though he did not know where he was going" (Hebrews 11:8). “So Abram went”. As Mary, daughter of Abraham in flesh as well as in faith, will answer “yes” to the divine call two thousand years later, Abraham responded to God’s command. It is an extraordinary acceptance. While he was a monotheist in a polytheistic society (we know from Joshua 24:2 that his own father worshipped idols), Abraham knew far less about God than did Moses, Jeremiah or Jonas. No miracles, no signs accompanied the call; just a promise to this childless man which must have seemed unbelievable. He simply obeyed. We know that he experienced terror on his journey – the opening line of Gen 15 has the Lord saying to him, “Fear not, Abram, I am your shield”. And, again. “As the sun was going down, a deep sleep fell on Abram; and lo, a dread and great darkness fell upon him” (Gen 15:17). He left Haran in southern Mesopotamia (now in modern Turkey) and travelled south-west across Syria and through Damascus. He probably followed the ancient trading route, the “King’s Highway”, from Damascus along the hilly backbone of Jordan and into Canaan. He crossed though Shechem (today the Palestinian town of Nablus) and Bethel; then south to the Judean desert where famine forced him south-west to Egypt and the fertile Nile Delta. After a sojourn in Egypt he retraced his steps through the Judean desert to Canaan, eventually dying at Hebron (where his descendant, David, would be anointed king nearly a thousand years later). The 1,500-mile journey (3,200 miles if one includes the route from Ur to Haran) had no obvious geographic conclusion. However, in the course of it, Abraham found the land which God promised to his descendants; his covenant with God was established; his long-abandoned hopes of a child by Sarah, his wife, were realised; and his name was changed from Abram to Abraham, “the ancestor of a multitude of nations” (Gen 17:5), the spiritual father of the world’s Christians, Jews and Muslims - half of the people alive on earth today. So this is not simply a geographic journey. Abraham could not grow spiritually while he remained comfortably settled in an idolatrous society, never moving out of his comfort zone. Pope St John Paul II, in a homily given on Wednesday, 23 February 2000, asked: "Are we talking about the route taken by one of the many migrations typical of an era when sheep-rearing was a basic form of economic life? Probably. Surely though, it was not only this. In Abraham's life, which marks the beginning of salvation history, we can already perceive another meaning of the call and the promise. The land to which human beings, guided by the voice of God, are moving, does not belong exclusively to the geography of this world. Abraham, the believer who accepts God's invitation, is someone heading towards a promised land that is not of this world." This Lent is an opportunity to leave our own comfort zones, and put behind us the many obstacles to our own spiritual journey. In a noisy world, we can try to be still enough to hear God's voice; and be courageous enough to act on it. Which evokes another quotation from Pope John Paul II: "Have no fear of moving into the unknown. Simply step out fearlessly knowing that I am with you, therefore no harm can befall you; all is very, very well. Do this in complete faith and confidence." |

AuthorHelen Gallivan is co-founder with John Dundon of New Pilgrim Path. This blog is adapted from ther book, Dawn without Darkness, published by Veritas. Archives

April 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed